The Origins of Jewish Ecology

From the Science, Religion, and Philosophy of a Desert People, to an Ecology of Humankind

“Philosophy is grounded on the presupposition that one sees the absolute in universals. In opposition to this, religion, when it has to define itself philosophically, says that it means the covenant of the absolute with the particular, with the concrete.”

- Martin Buber, The Eclipse of God, 1952

This is the first part of the three-part finale to our series on the human niche. If you have not read the previous article in this series, you can do so here. In this three-part article, coming out over the next few days, we will explore the origin of my work here on Jewish Ecology — moving from scientific community ecology into an integrated ecological and philosophical history. Through recounting the journey which led me here, weaving the story of my personal growth as a Jew, a scientist, and a philosopher, into the wider story of the Jewish people as a whole, I will reveal the foundational ideas that brought this blog to life. Together, we will wander through the historical roots of patriarchy, racism, and otherworldly philosophy, ultimately to show how human ecology – from the various niches we occupy to the stories and identities we carry – roots us in our relationships to community, the biosphere, and the cosmos. These two narratives — from myth to science, and from ancient mysticism to modern ecological awareness — serve to set the scene upon which a new integrative portrait of human ecology can, quite literally, be drawn (coming in part three of this article). I hope you join me as we journey through Jewish Ecology and explore the contours of the human niche.

Growing up in a reform Jewish community, I noticed that, unlike most religious institutions, science and myth were not seen as necessarily at odds with one another. We were always encouraged to ask questions, and to critically evaluate how and when religious rules no longer applied to the modern day. The existence of a divine power, a personal God, never quite made sense to me – I had been raised to trust science, and the miracles and otherworldly happenings of the Torah seemed far more like a fantasy book than anything that could actually happen. I have long struggled to comprehend the meaning of God.

I recall one morning, sitting in Sunday school and hearing about the various naturalistic ways that the 10 plagues of Egypt might have occurred. This is the only way that the stories of the Torah, in their Truth, ever seemed coherent to me – and from this perspective, the line between literal meaning and metaphor becomes increasingly blurred.

The biblical creation narrative, unfolding over seven transformative days, also posed a real challenge to my belief in G-d. Yet, my rabbis encouraged us to approach the story from the perspective of G-d – after all, a day for G-d might look like a billion years for us. From this perspective, science no longer seemed to oppose the Torah. Modern scientific cosmology, with the big bang, cosmic evolution, and the eventual origin of humankind, seemed to find some of the biblical accounts of creation to be rooted in reality. After all, “Let there be light”, could represent the Big Bang (Genesis 1:3). While I now know that, unlike the opening of Genesis, the evolution of plants came after the evolution of fish, this naturalistic openness helped me see that some of the biblical accounts of creation coincide with scientific consensus. As a child, I was open to the idea that perhaps, G-d is the spontaneous unfolding of the goodness and the natural world.

For me, Judaism needs to be grounded in naturalism, in the real world. But with so many of our most potent stories full of supernatural powers and miraculous events, my interest in myth was soon eclipsed by my passion for scientific explanations. Since childhood, I understood that science can’t definitively prove or disprove G-d’s existence; I remained open and uncertain, agnostic towards G-d. My Judaism drove me to study, to question, and to celebrate life – with Jewish spirit burning inside me, questions of G-d’s existence became unimportant.

I got older, and soon I stepped into the halls of academia. Peering into the many faces of science, I stopped worrying about G-d entirely. Instead, I wondered about life, our evolution, and how our creativity and habits shape our communities. And I wondered about our relation to other species, and the Earth as a whole. And further, I pondered whether life matters to the rest of the cosmos.

Even without a relation to G-d, I never once doubted my connection to Judaism or my Jewishness. Science had simply driven G-d out of view, behind the rational coherence of human knowledge – and what good is a G-d beyond our grasp? We lack the words to describe how G-d relates to our living world. I’m still unsure what words to use to describe That which is beyond language. But what I do know, is that G-d is One.

When the Torah is brought out, we sing: “It is a Tree of Life to them that hold fast to it, and all of Its supporters are - Happy!” This has always resonated deeply with me. I have always held fast to the Tree of Life – though, since I first learned of evolution, this Tree of Life has looked more like the one linked here (try zooming out from here!). G-d is the Oneness of the Tree of Life, the living force which moves through all of us . And more, G-d is the life that exists beyond our narrow definitions of life – but this idea remains beyond what is comprehensible, and until very recently, it would have come across to me as artful meaninglessness .

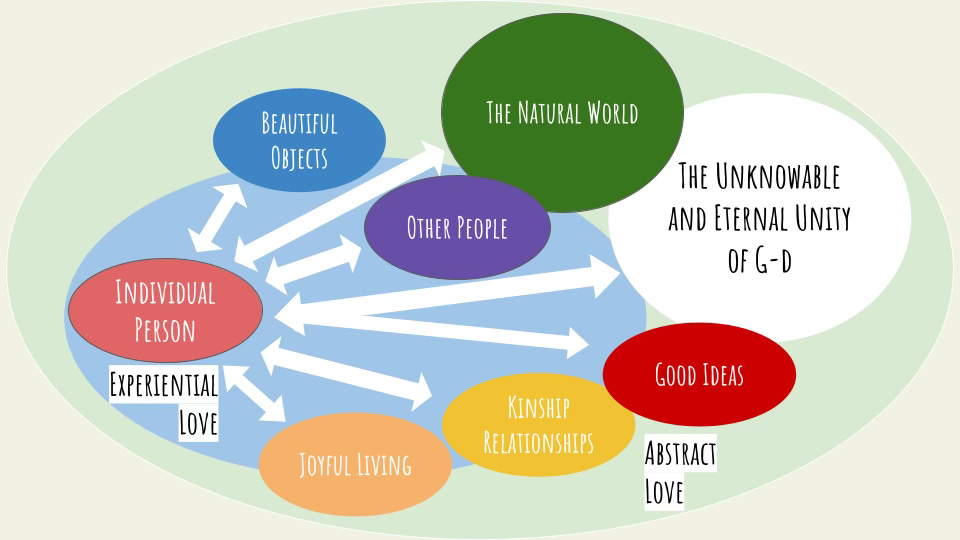

My return to G-d began two years ago, on a sunny spring day. While pondering natural philosophy and human ecology, deep in the book Uncommon Ground — something clicked. I had a realization: G-d, nature, love – each of these words encapsulates the same essential relation, the same unitive approach to reality. This realization brought me to return to encounter the heart of the Jewish faith: a love for existence that penetrates deep into the human heart and mind, and forever endeavors to take greater responsibility for all of one’s relations and obligations in the world. As soon as this “ecology of love” was revealed to me, I sketched out the contours of the scales of these relations. I soon rediscovered the transcendental love of G-d or nature, which has never ceased to permeate both my scientific studies and my passion for the living world.

A very similar diagrammatic approach to the ‘Ecology of Love’ lies at the center of the article “Defining Love within Ecology and Judaism”. By mapping out the various "objects" we can love, the immanent transcendence of love can be understood as grounding all our passions and care.

As an ecologist, since before I first peered through a hand lens at the minute details of a flower, as I was first beginning to notice distinct plant communities coinciding with the various impacts of human and non-human actions, I strived to comprehend the meaning of the word “nature”. Why was it that I had to go somewhere to be “in nature”. And what about our “inner nature”. Or “human nature”? Through the ecology of love, I began to understand the sheer power of this word – stretching from the tiniest details of a person to the whole expanse we call the cosmos. When we love nature, we love life: our whole existence. G-d?

Growing up today, it seems like nature is always counterposed to civilization. Upon entering a wilderness area, I would often remark jokingly: “welcome to nature!” This duality – between nature and culture, wilderness and civilization – plagued me through college. I could never quite understand why some areas feel so devoid of nature, and why, even as plants burst forth from sidewalk cracks, people see nature and culture as entirely separate .

After my junior and senior years of college, I had the opportunity of working at a long-term ecological research area, where, for ten weeks at a time, I would work in an isolated station, in a desert, with another scientist on both my own research, and a large-scale field experiment. During this time, I had plenty of time to read, write, and think. What is nature? What is culture? These were the inescapable questions that beset me as I dwelled in the desert. For 20 weeks over two summers, I studied the ecology of this harrowing place: the land Spanish conquistadors called “Dead Man’s Journey”; the Jornada del Muerto Basin.

Three photos I took during my time at the Jornada del Muerto Basin. During the monsoon season, life surges forth from this otherwise dry landscape. Top: A distant monsoon passing at sunset. Middle: Part of the research site on which I worked, with a distant monsoon and a double rainbow passing over the Doña Ana mountains. Bottom: The desert in vivid color after a wet July. A butterfly can be seen passing between honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) shrubs and fields of blooming many-bristle fetid-marigolds (Pectis papposa).

Driving in over 20 miles of straight dirt road, punctuated by cattle-guards, property boundaries, I could imagine I was passing into nature. Yet the line between nature and culture is always an illusion – yet sometimes an illusion enforced by violence: reinforced by gates, border regimes, and claims of ownership. Even so, they are perpetually transgressed: nature is uncontainable, life is always entangled with other life, weaving across species boundaries, piercing through cell membranes and cell walls. There is no separating social from natural history. Humans always shape their homes; human-ecosystem relationships, symbioses, and environmental change are all foundational to human life.

During my second summer in the desert, I stumbled across a book that transformed my understanding of human civilization. Arthur Lovejoy’s 1936 book, The Great Chain of Being, outlines the history of its titular idea: a cosmic hierarchy in which everything has a place. From the lowliest of minerals, through plants and animals, women and men, to the highest of ideas – the Good, or G-d – the Great Chain of Being attempts to show the divine blueprint through which G-d ordained the cosmos. From this book, and the arcane history it bears witness to, I first witnessed the esoteric chaos from which modern scientific ideas of the cosmos emerged. By focusing on the “Great Chain of Being” as an idea rooted in Plato and Aristotle, Arthur Lovejoy highlights how the philosophical construction of a cosmic hierarchy enabled humankind to imagine itself precisely between the living world, and the angelic world above: right between mind and body, heaven and earth, intellect and instinct.

The “Great Chain of Being” was the backdrop over which I developed my own understanding of human ecology and the distinct niches we occupy. On the one hand, I yearned to be free of this divinely hierarchical vision of the cosmos, but on the other, I wished to preserve the understanding that we, humankind, fit in a uniquely diverse and an extraordinarily special place on the Tree of Life.

“The greater number of the subtler speculative minds and of the great religious teachers have, in their several fashions and with differing degrees of rigor and thoroughness, been engaged in weaning man’s thought or his affections, or both, from his mother Nature”

- Arthur Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being

And unlike Plato and Aristotle, and many who came before and after them, I still firmly believe that all life, humankind included, is fundamentally a part of Nature, a leaf on a branch on our great Tree of Life. There is no “weaning” ourselves from the natural world without destroying the living ground for our continued existence.

This article, unfolding over three parts, traces the journey that culminates in this unique religious-philosophical-scientific synthesis: Jewish Ecology. By connecting the evolution of Jewish culture to the integrative niche model I developed in the desert, I hope you will see the fundamental contours around which much of our future endeavors here will unfold. I hope you enjoy.

Jewish Cosmology and its Ecological Niche

Judaism is an agricultural religion. Our ritual cycle is embedded within an agricultural calendar – synchronized with the turning of the seasons and the timing of the rains and the harvests. With the start of the year, we purify ourselves before G-d, ensuring that the winter rains will bring us good harvest in the year to come. With Sukkot, Pesach, and Shavuot, our festivals remind us, no matter where we are or what we do to live, of the harvests. Torah is rooted in this cyclical agricultural tradition, embracing at once the cycle of the year and the forever changing flux of generations. Where to begin with Jewish ecology? The Judean foothills? The land of Israel? No.

We must begin with Cain and Abel. Sons of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel were born not in the paradise of Eden, but somewhere in the floodplains of Mesopotamia. Cain took to agriculture, Abel to shepherdry. Each son sought to earn G-d’s favor through a noble sacrifice: Cain, the fruits of the land; Abel, the firstborn of his flock. For some reason or another, G-d had respect for Abel’s offering, and not Cain’s. The rest of the story is history: Cain killed Abel out of envy, G-d warned Cain that the earth will not easily not willingly give up “her strength” to him. He flees as an outcast east of Eden, eventually founding the first city, named after his son, Enoch.

This story, though rooted far more in symbolic truths than historical ones, highlights the tensions that arose as the people of Mesopotamia adapted with climatic and demographic changes – as hunter-gatherers were slowly displaced by farmers and shepherds. As Anthony Sattin puts it, in his book Nomads, the story of Cain and Abel “highlights one of the consequences of the Neolithic Evolution, the conflicting interests of herders and tillers, nomads and settled.” As the foundational stories of Judaism were first being told, their authors bore witness to dramatic transformations in the structure of human and non-human communities.

But this period of transformative social and ecological evolution is not solely underwritten by various means of subsistence. The transformation of hunter-gatherer societies into agricultural and pastoral ones was a slow and gradual transition, drawn on by domestication – a niche constructing process – and shifting baselines in what ecosystems could provide and societies would expect (Zeder, 2016). Ultimately though, across centuries and millennia, we can recognize the deep changes in social norms, social geographies, and spiritual outlooks that resulted from it: the neolithic (r)evolution. This can perhaps be seen most clearly through the conclusion to Cain’s story: the origin of the city.

Cities play a prominent role in the formation of Judaism. Out of the idolatrous city of Ur, Abraham fled with his family, leaving behind towering walls and polytheistic stories of how the world came to be. Abraham was called forth by G-d, told that he had a great destiny awaiting in the distant promised land. And so he went. Out of the land of managed rivers and many cities, and into a land of erratic rainfall and many peoples, Abraham joined them, with their tent villages, varied hunting, farming, and herding traditions. Yet, he never forgot his idol-smashing character.

Even before Abraham, in the earliest Mesopotamian city-states, diverse stories from many cultures were invoked to explain the cosmos. One story, arising from pre-historic roots in the Proto-Indo-European culture, propagated a distinctly hierarchical vision of the cosmos: Two Gods at the beginning of creation, Manus and Yeemnu. Manus sacrifices Yeemu and uses their body to create the world. Yeemu’s body creates the soil, water, and air; their hair creates the plants; their bones, the stones of the Earth. The human community too was made from the body — the king from the whole body; the priests from the head; the warriors from the arms; the farmers from the legs. This story upheld the social structure of Indo-European and later Mesopotamian civilizations, subordinating human life to the will of the king and the priest, palace and ziggurat: a collective endeavor for cosmic wholeness.

Unlike the cosmologies common to the circumstances he fled, Abraham didn’t see humankind naturally divided into social roles. After his long journey west, he took his place in Canaan among the farmers. For the Jewish forefathers the roles of priest, warrior, and farmer were not distinct: these responsibilities all fell to the common man.

The Origin of Yisrael

Like the story of Cain and Abel, the tale of Jacob, patriarch of the 13 Hebrew tribes, also bears witness to the rising tensions between the new ways of living – and the varied ecological niches they represent. Jacob, son of Isaac, son of Abraham, was the second son of Isaac, heir to Abraham’s covenant and the promised land. Esau, his older brother, was a hunter of great skill; Jacob a farmer. Social norms of the time meant that Esau, first son of Isaac, was to receive his family’s birthright: household leadership and a double portion of paternal inheritance. Jacob betrayed his brother and deceived his father — he impersonated Esau, tricking his father into giving him the inheritance.

Again, in this tale, we see cultivators of the land prevailing – though not without injury. Esau was furious with Jacob, and vowed to kill him. Rebecca, Jacob’s mother, warned her son about this threat, driving him to flee to spend the next years with her family. Jacob spends 20 years there, finding a wife, and starting a family. Eventually though, he decides he must return to Canaan. He sends gifts with messengers, aiming to appease Esau into reconciliation. On his journey home, he has a fateful dream. In it, Jacob wrestles with an angel. His hip is knocked out of its socket, yet he wrestles on. At daybreak, the two are still wrestling. Jacob fights on, not wanting to yield until he earns the angel’s blessing. The angel asks Jacob his name – only to tell him that his name is Jacob no longer. He is Israel, for he has wrestled with men and with G-d, and he has overcome. He asks the angel again His name, but He is silent. Instead, he receives His blessing.

Jacob, now Israel, goes on to reconcile with Esau. Rabbi Rami Shapiro describes this encounter in his book Judaism without Tribalism.

“Esau's anger and Jacob's fear both disappear, and the two brothers fall into each other's arms, weeping in reconciliation (Genesis 33:4)…After a while, Esau offers to travel at his brother's side. Israel turns down the offer, saying, ‘You walk at the pace of a warrior, while I travel at the pace of the young and the nursing among my family, flocks, and herds. If these were driven hard for even a single day, they would die’ (Genesis 33:13).”

Jacob was transformed by his dreamtime encounter with the Divine — the wound he received from his G-d-wrestling humbled his demanding spirit — becoming a new man capable of tending to his family, his animals, and the land. He becomes an earthly man bound to his relationships and place on Earth. G-d’s presence all around him.

This story reveals the deepest truth of what it means to belong to the people Israel. While generations passed, and soon Israel became the name of a kingdom, Israel, at its etymological root, remains essentially a verb: to wrestle with G-d. Be it through tending the soil, caring for one’s flock, or loving one’s neighbor, to be Israel is to struggle with G-d and one’s community, and to emerge evermore understanding, wise, and compassionate. This struggle lay at the core of what I was doing while wandering at the Jornada del Muerto, pondering the meaning of nature and G-d, and our place – our niche – here in the world.

To understand then how we went from Israel as a divine idea to Israel as a worldly nation – barely distinct from other nation-states – we must first understand how Jewish notions of Divinity evolved within the political, spiritual, and ecological context of the Jewish diaspora.

You can read the second part of this three part finale on the human niche and Jewish ecology here! I hope you enjoy!

Thank you for reading Jewish Ecology. This blog aims to build a participatory dialogue in which important ideas at the intersection of Judaism and ecology can help us root ourselves in the World. This blog is not just for Jews; I aim for these articles to be accessible and impactful for anyone that is interested in building up an understanding of the role that spirituality, philosophy, and/or ethics play in bringing about a more peaceful, ecological, and sustainable future for all People and the World. If you can think of someone who might enjoy these articles, please consider sharing this blog!

Works Cited:

Buber, Martin. The Eclipse of God: A critique of the key 20th century philosophies + Existentialism + Crisis Theology + Jungian Psychology. 1952.

Lovejoy, Arthur. The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea. 1936.

Sattin, Anthony. Nomads: The Wanderers who Shaped our World. 2022.

Shapiro, Rabbi Rami. Judaism without Tribalism: A Guide to Being a Blessing to All the Peoples of the Earth. 2022.

Zeder, M.A. “Domestication as a model system for niche construction theory” in Evolutionary Ecology. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-015-9801-8