Transformations in Jewish Ecology

How the G-d of Israel became an Otherworldly King of the Cosmos, and How Jewish Spirituality Evolved to Maintain its Soulful Connection to the Living World

“What our most holy prophet, through all his regulations, desires most is to create unanimity, neighborliness, fellowship, reciprocity of feeling, whereby houses and cities and nations and countries and the whole of humankind may advance to supreme happiness.”

- Philo of Alexandria, On the Virtues, circa 30 CE

This article is the second part of the three-part finale of our series on the human niche. If you missed the first part, you can read it here. In this three-part article, we are exploring the origins of Jewish Ecology, moving from ancient Jewish history to our modern ecological crisis . Through recounting this tale, I am building up to reveal the foundational theory which brought this blog to life. We will then examine a brief history of Jewish thought: beginning with myth and ending with ecology. In this part, we will examine a key cosmological framework through which patriarchy and racism became imagined as natural, which will open up a gap through which we can reimagine our place in the world. I hope you join me as we journey through the Jewish Ecology and arrive at the human niche.

Israel: From Patriarchs to Kingdoms and Prophets to Temples

The last part of this article concluded with Israel – the sublime concept of struggling with G-d – teetering on a knife’s edge, soon to be reduced just another name for a nation. As Patriarchs gave way to Judges and Judges to Kings, the people of Israel transformed from a coalition of related tribes into a bonafide nation. Tribal and ancestral ties still rooted individuals to particular places and social roles, but increasingly, one’s tie to G-d stood as a monument, reigning supreme over all other relations. During this period – extending over nearly a millennium – Jerusalem and the priestly caste in charge of its temple, took an increasingly central role in the religious traditions of the land of Israel.

The kings over Israel were not to be like the kings over other kingdoms. Following in the same tradition as the rule of the judges, the king was meant to stand in direct relation to G-d, acting as G-d’s hand, ruling over G-d’s people. In this way, the Kingdom of Israel remained a theocracy – quite literally, following rule by G-d. And yet, David’s kingship fails to live up to the ethical demands of G-d’s covenant with the people of Israel. Like Abraham the Patriarch before him, David continued to lord his power over women and servants, normalizing patriarchy and slavery. The very premise of lordship — like a shepherd to their flock, founded the basis of early Jewish visions of G-d and cosmos.

From the rule of Judges to that of Kings, through exile and occupation, Jewish prophets spoke Truth to power – rendering hollow the divine right of human kingship, and reminding the people that G-d, and our covenant with Him remains supreme. The prophet Nathan, chief advisor to David, son of Saul, the first king of the likely mythical united kingdom of Israel, was not afraid of condemning David when his actions betrayed the Word of G-d. Nathan confronted David after he slept with the woman Bathsheba — later to become mother of the next king — who then orchestrated the death of her husband, Uriah. The prophet spoke in parable, telling of a rich man who took a poor man's only lamb, enraging David. But Nathan told David: You are the rich man, guilty of a far greater sin. He made it clear that no earthly power, not even that of a king, is above the Divine law (2 Samuel 12:7).

The Jerusalem Palace and Temple may have commanded the people’s ritual obligations, from Nathan and Isaiah to Elijah and Jesus, the prophets reminded them that G-d’s covenant does not begin or end in rituals centered at Jerusalem, but in the whole of our lives, and in all our relations.

Much like the great wall around the ancient city of Uruk, which "separated the regulated, man-made, urban environment from the unbridled forces of nature" and divided the forward-thinking, sedentary people from the diverse, primal world outside, the centralization of worship in the walled city of Jerusalem created a symbolic divide (Sattin). It marked the separation between the officially sanctioned religious practices of the city and the more diverse forms of worship that persisted elsewhere. Just as Uruk’s wall delineated a new social order, the rise of Jerusalem as the spiritual center of the early Jewish ritual life represented a consolidation of religious authority, hegemonically shaping the spiritual and cultural center of the burgeoning religious tradition.

Modern Judaism remains inseparable from Jerusalem, Whether as a spiritual ideal or a worldly city, Jerusalem represents spiritual aspirations of the Jewish people, yet in the history of the Hebrew faith, this was not always true. In the centuries before the Babylonian exile, Judaic religion was inseparable from oral tradition and ritual. The temple stood at the center of these rites, but after its destruction, Jews had to turn elsewhere for a spiritual center.

Before the age of Hebrew kings, Jerusalem was but one of many temple sites. One such temple site, at Tel Arad, stood quite similar to the temple in Jerusalem. Yet, within its Holy of Holies – the chamber at the center of the temple where the priestly caste would administer their ritual offerings – stood not one, but two standing stones. These stones represent the presence of G-d: one representing the masculine face of the divine, YHWH, and the second representing the female face, Asherah.

The word Asherah is used over 40 times in the Torah, yet over time its interpretation has changed – from the name of a 15th century BCE Semitic maternal nature G-ddess, to a word for a tree, grove, or sanctuary. Often, in places where G-d’s presence was felt on Earth, often atop hills or under great trees, pillars would be set up to denote the holiness of the location (Genesis 28:12). These pillars would later be called Asherot (plural for Asherah), and would act to mark places overflowing with Divine presence (Barker). Yet, during the religious reforms of King Josiah, all these Asherot, including the Asherah housed within the Jerusalem temple, were burned (2 Kings: 22-23). The divine feminine was being purged from the Judaic faith. YHWH, with His many names, would soon be the universal Divine lord, ruling over the people Israel.

According to Deuteronomy 12:5-6, worship at temples outside Jerusalem was strictly forbidden. We cannot assume that worship elsewhere immediately became universally understood as clandestine or subversive – most likely, it is the Jerusalem priesthood that is responsible for writing these verses of Torah. Worship through sacrifice was not universally accepted, and Jewish ritual life remained diverse – the Essenes, whose practices and communal lifeways are attested to in the Dead Sea Scrolls – were prohibited to sacrifice animals.

“Israel’s sacrificial cult may have originated in the primitive need for a living communion with God through some sacramental act, such as a communal meal; undoubtedly, this was soon complemented by a quite different feeling: the need for a sacrificial offering that could symbolize, as well as proffer, the intrinsically desired and intended self-sacrifice. Under the leadership of the priest, however, the symbol became a substitute.”

- Martin Buber in On Judaism

Regardless of how we ended up with the orthodox laws we know today, it is undeniable that what we know today as “Jewish history” is but one group’s narrow retelling of the story through which this rich spiritual tradition evolved.

Through the act of compiling songs, stories and laws into scripture, ancient Judaic scribes constructed a spiritual niche upon which future Jews would struggle to relate to the world. The creation of Torah, along with the Halakhic laws within it, is thus the foundational act of niche construction through which Jewish existence – both religion and culture – must be understood. The exile of the divine feminine from Judean scripture reveals the long lasting impact that local power has left on the Scriptures that have been passed on to us – continuing to tarnish the received scriptures of all the Abrahamic religions of today.

“The greater number of the subtler speculative minds and of the great religious teachers have, in their several fashions and with differing degrees of rigor and thoroughness, been engaged in weaning man’s thought or his affections, or both, from his mother Nature”

- Arthur Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being

G-d was to be an otherworldly artificer, the world His Book. Mother Earth became merely the dominion of this masculine lord, or worse, perhaps she was ours to rule over in His stead. From the Babylonian exile and the conquest of the Assyrians and Persians, all the way to the Greek and Roman occupations, through the rise of Christianity and Islam, all the way to today, G-d, both as an idea and as reality, has become an all powerful king, whose masculine lordship is as absolute as it is otherworldly. In this cosmological image, humankind is as hierarchically ordered as all of nature – with G-d above and Earth below, and in between, human society a well ordered chain of subservience. While we may all be part of this unified world-system, G-d and man remain above the rest of Nature. Oneness – key to recognizing that humankind lives among the living world – thus became useful as a totalitarian idea, enforcing the rule of tyrannical lords over their “natural” dominion.

One depiction, very similar to that promulgated by the rational mystic Rabbi Moses Maimonides, of the “Great Chain of Being". In this case, it coincides most closely with the gradation of being described by Aristotle and popularized again in the Renaissance. Portrait from “The Wholeness of Nature Reflected in the Mirror of Art", from the first volume of the Christian Kabbalist Robert Fludd's Utriusque Cosmi … Historia, 1617

The Living Implications of the Great Chain of Being

As Jewish ideas regarding the oneness of G-d percolated into philosophy, scholars from across the world struggled to reckon with the radical oneness that Jewish monotheism asserts. As Jewish theology evolved into Christianity and later into Islam, and as these Abrahamic monotheisms spread around the world, new metaphysical schemas and cosmologies were postulated, debated, and dispersed across communities. Neoplatonism was one of the first Christian doctrines to seek a mystical and integrative understanding that linked the Oneness of G-d and the multiplicity of the natural world. From the heavens above to the human below, this new schema sought to explain the whole of existence through the hierarchy from divine to profane — with lord over peasant and man over woman at its most worldly heart. Whereas Islamic philosophers used this chain to show man’s place precisely where existence and consciousness meet, Christian kingdoms went on to use this schema to dehumanize black and indigenous peoples, ruling over society as if it were their Divine right.

The Great Chain of Being, as illustrated by Didacus Valades, Rhetorica Christiana (1579). In this portrait, we can see a chain extending from the Divine down through angels, humans, animals, plants, down to the earth.

This hierarchy — of Good on top and Evil at the bottom — mirroring the Christian cosmology of Heaven and Hell, slowly crept into the social structures of “holy” kingdoms and colonial empires: an ever-widening gap between the monarchy and upper class, and the increasingly othered beings living at the bottom.

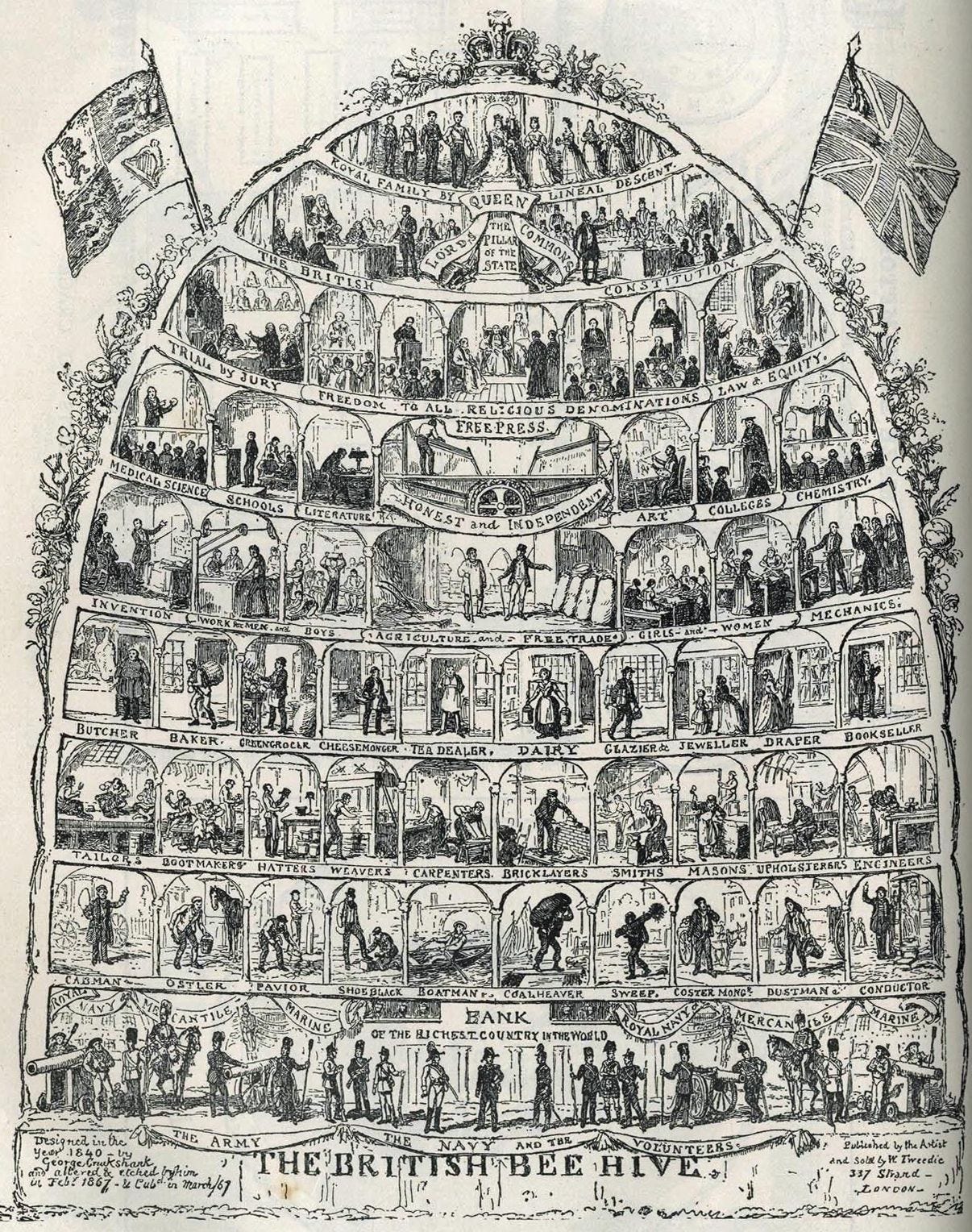

Two paintings depicting the social implications that the naturalization of the hierarchical “Great Chain of Being” had on human life. Top:A Castas painting by Jose Agustin Arrieta, an 18th century artist outlining the racialized hierarchy of Colonial Mexico. Bottom: A painting by George Cruikshank depicting late 19th century Britain. In both cases, those with power sit on top, and each person has their natural place in the social regime.

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life

In this increasingly open-to-interpretation landscape of mystical philosophy, Kabbalah offered Jews a path to reckon with their received cosmology. By struggling with old texts and new, and digging deep into the metaphorical and symbolic meanings of these books, Kabbalists came to a radically new vision of the relation between G-d and world. Building on Maimonides, and perhaps other portraits of the great chain of being — sketched by Islamic philosophers and Neo-platonic mystics — the Kabbalists outlined a vision of the G-d and Nature intertwined, in which the source of all creation stems from the divine overflow of G-d’s infinite into the World.

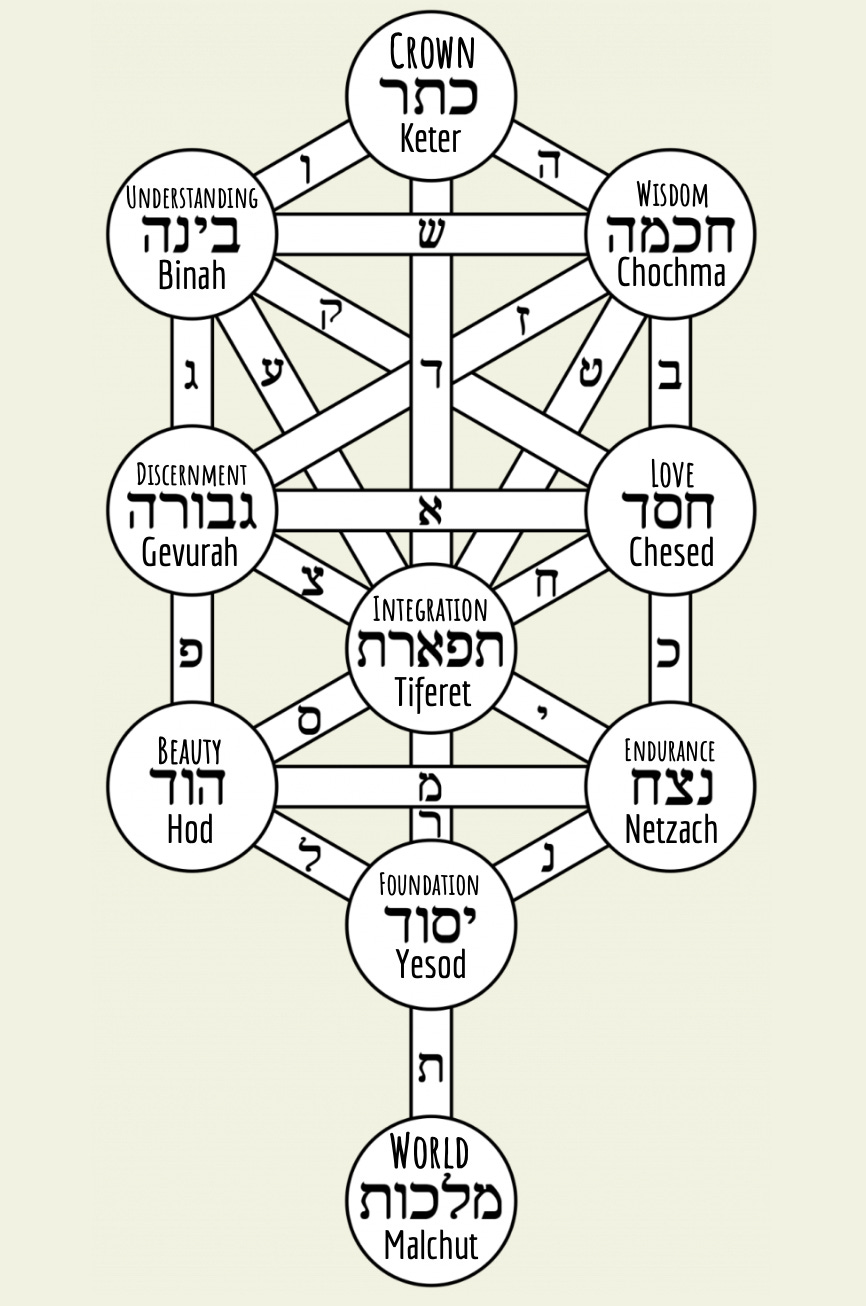

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life brings together the 10 Sefirot, each emanations of G-d. Keter, the crown, is the highest and most ineffable of these Sefirot, often linked to G-d’s unknowable Will. Beyond Keter lies the Ohr Ein Sof — the Light without Limit. Beneath lie characteristic manifestations of the divine we might recognize — wisdom and understanding, loving and discernment. At the bottom lies Malchut, kingdom. This is often understood as the natural world.

The 10 Sefirot arranged into the Tree of Life. Each Sefirah is tied to numerous symbols and meanings. The interpretations of these meanings, shown here, come from my own studies.

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life links the ineffable, unlimited nature of the Divine with G-d’s physical presence, G-d’s life, here on the Earth. And yet, beyond these emanations, G-d remains infinitely beyond our comprehension. From the unknowable and transcendent infinity of Keter and beyond, to the natural world in Malchut, G-d is interfused with all existence. While the Kabbalistic Tree of Life thus breaks the Great Chain of Being – revealing the whole world-system to be penetrated by G-d’s Holiness – the apparent hierarchy of a transcendent idea over the physical world remains intact. Jewish Ecology seeks to overcome this limitation. To do this, we must reinterpret the Divine values present in the 10 Sefirot vision in the light of human ecology, finding their place within evolution of the human niche in its integrative wholeness.

Click here to turn to the final article of this series, where we will complete this journey through Jewish ecology.

Thank you for reading Jewish Ecology. This blog aims to build a participatory dialogue in which important ideas at the intersection of Judaism and ecology can help us root ourselves in the World. This blog is not just for Jews; I aim for these articles to be accessible and impactful for anyone that is interested in building up an understanding of the role that spirituality, philosophy, and/or ethics play in bringing about a more peaceful, ecological, and sustainable future for all People and the World. If you can think of someone who might enjoy these articles, please consider sharing this blog!

Works Cited:

Barker, Margaret. “What did King Josiah Reform?”. Forum Address given to BYU, May 6, 2003. Link to article.

Buber, Martin. On Judaism. 1967.

Lovejoy, Arthur. The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea. 1936.

Sattin, Anthony. Nomads: The Wanderers who Shaped our World. 2022.

I felt so bad that I dropped all my comments on Reddit, I wanted to drop one here, haha!

Reading through this I did notice and love the equation between the Oneness-doctrine and the centralization of power around, well, technically a god, although in practice, of course, oftentimes an emperor or king - If you ask me, in discussing the movement towards the idea of a single, unitary god, it's a great critical awareness to have, especially working with mysticism, which I think, while it certainly is rich in Oneness (which is still an idea I tend to like, despite it's use for political manipulation), I think the mystic disciplines, like Kabbalah, or Merkavah, Sufism, the ways of the Church fathers, and so on, really do a good job of paving the way for the less 'political tool' and more human-spiritual aspects of it!

Thank you for this work! I’m on a similar journey, working within the Christian tradition.