Defining Love within Ecology and Judaism

Judaism is a religion centered on loving our neighbors, loving G-d and using this love to direct action towards goodness. But what is love? And how does love connect us to the natural world?

Through this blog, I aspire to bring interdisciplinary scientific perspectives into direct contact with the Jewish tradition. This requires conceptual clarity that is rare on the internet. The first step to making this a reality is to clarify and ground key concepts as they connect Judaism and Ecology. While my personal journey might have begun within the notion of the ecological community, my first self-guided steps into interdisciplinary ecology began with the concept of “Love.” I hope you will join me as we think through the concept of love, and grapple with the connections between love, ecology, Judaism, and the our collective relationship with the world.

What is love? This is a question that likely concerns us all. And yet, very few of us likely feel like we have a real understanding of love. This is a question that I did not intend to ask, but through a sudden realization, I came to the fundamental insight that within the Judaism I was raised with, Love, Nature, and G-d all carry the same weight – a connotation of divine connection between the self and others beyond our full comprehension. This sudden realization came about while reading Uncommon Ground, a collection of essays created when diverse scholars convened for a 10 week weekly seminar examining the social construction of the idea of “nature.” While reading Giovanna Di Chiro’s essay Nature as Community: The Convergence of Environmental and Social Justice, I came to appreciate the way that various Jewish teachers across my life had taught me to care deeply for the natural world by invoking a particular understanding of G-d. G-d here is not some anthropomorphic deity, but rather the force of face-to-face connection, which emerges as two or more people open themselves up by really listening to one another. In this way G-d can be found in the process of evolution, as ecological interactions evolve into symbiotic coevolution. And in this very same way, Love is the force by which we open ourselves to other beings, positively affirming the transformative space that emerges within the relationship, and actively collaborating to create positivity in the world.

As I came to this new understanding of the role of love in structuring our relationship to both nature and G-d, I sought to learn the various relationships which structure healthy human development. I began by considering the trajectory of my own life. As I have grown into an adult, the environment and relationships in my life have left a deep impression on the person I am and am becoming. This evolved into a seminar course I developed and taught at university titled “The Ecology of Love: A Transdisciplinary Exploration of Love across Scales.” This class provided me the chance to build a learning community in which students of any discipline could explore the biology, philosophy, and spiritual dimensions of love in the world. The rest of this article will now work to lay out my current understanding of love as it relates to how we interact with others in the world.

We are social beings, and our life is inseparable from the community in which we live. Although our present divisions may lead us to think otherwise, human beings have always been a species deeply concerned with the wellbeing of others. Through examining the concept of love, I hope to show how our actions are guided not by selfishness, but by our sense of love, interdependence, responsibility, and the care we carry for those close to us.

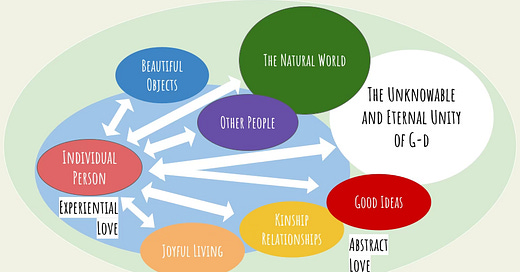

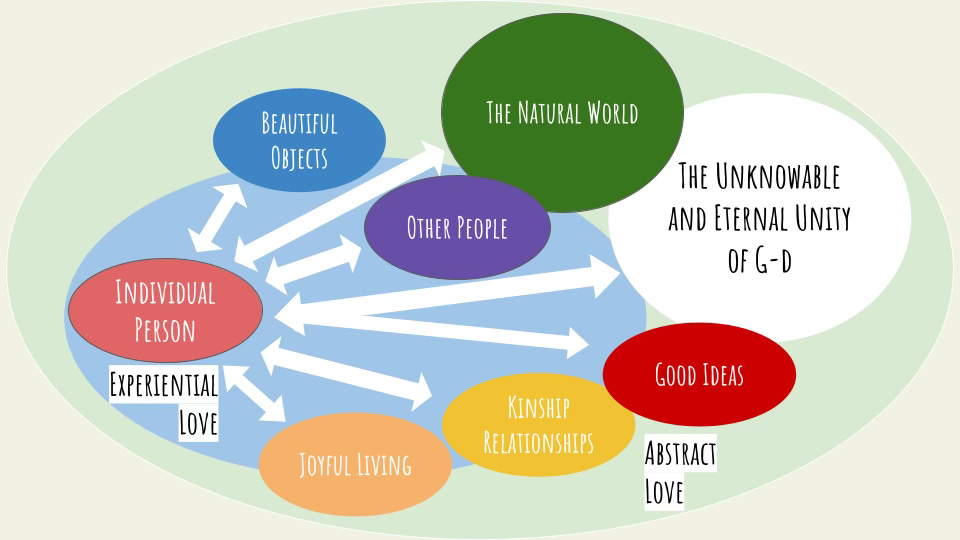

Love is more than an emotion, though it can inspire emotions of all sorts. Love is inherently connective. It drives us towards self-transcendence and selflessness. Before delving into the ecological relationships which love permeates, we need to recognize the verbal directionality of love and the relationship between language and lived experience: the relationship between lover and loved. Love is a concept we learn through stories and language. While love can be directed towards people, places, things, and ideas, more often than not, our image of love is grounded in romantic fantasy. But what do we really mean when we say we love something? How do our evolved faculties predispose us to feel love? How does love bring a human body into a fundamental relationship with others in the world?

These questions cut to the core of the relationship between the lover and the loved. The nature of that relationship is one of attachment – in which the individual self becomes intertwined with objects of their love. Attachment spans the space between rigid notions of self and other; blurring the egoic line between me and not-me, mine and yours, private and shared. Through love, the individual person comes to know themself. In loving relationships, the desires, passions, and values placed upon us by inherited tradition can be affirmed or denied. In love, the personal quest for individuation becomes a shared space of creativity and belonging. Through love, we aspire towards understanding the soulful depths of our loved ones. By invoking a sense of concern, love catalyzes wonder into curiosity and transforms freedom into responsibility. Love is the positive passion which drives us to embrace others as vital to the identity, wellbeing, and thriving of the individual self.

Beyond my own personal experience, Judaism is a religion built of love. Within Jewish practice, daily prayers affirm the oneness of G-d, G-d’s love for the world, and our love for G-d. But beyond this daily practice, each Jewish person’s lived relationships to Judaism builds upon the shared stories, values, and debates carried on in our communities for generations. Within this textual tradition, love remains the essential ingredient through which the rigid doctrine of mitzvot (obligatory good deeds) becomes imbued with a sense of ethical responsibility and care. Regardless of the varied ways this love has been channeled, it transcends a passive sentiment about the world; it is essential to the way we relate to our neighbors, build communities, and maintain a sense of Jewish identity.

From an ecological and evolutionary perspective, this love is not something we have simply through divine providence. Our sense of love has evolved in relation to our inherent sociality – from our earliest days on the planet, we rely wholly on the parents, caretakers, and broader community in which we are raised. But while the case of human love may originate in mammalian reproductive needs, human love is distinct from the mammalian attachment system. Although our attachments remain grounded primarily in lived experience and face-to-face relationships, our ability to abstract our experience into broadly inclusive concepts allows us to begin to shift the focus of our love beyond parental and reproductive relationships. As we come to know ourselves as living organisms, social animals, human beings, and/or divine manifestations, this abstraction helps us to extend our empathy to other beings. In this way, love can be understood as something we possess that extends compassion and concern for others, and yet it is always limited by the ideas we carry about ourselves and our kin.

Love brings individuals into dialogue with the world through extending compassion and concern beyond the self and by grounding lived relationships in the understanding of interdependence.

If love is truly grounded in our extensive ability to form attachments to others in the world, then all relationships built upon commitment, honesty, trust, and responsibility are inherently loving. We may love the animals, people, and the central ideas through which our daily lives unfold, but this love ought to be extended to the land, soil, water, and air which provide us ground and sustenance for our continued existence. Our ability to form attachments is rooted in our biology: our existence as mammals ensures that we have the capacity to attach to maternal providers, but our life as humans reveals that our attachments can go much deeper. We have evolved the capacity to care deeply about our kin and our community, as well as the place we call home. The challenge within human existence lies within the central place of communication and understanding in driving the expansion of our love in regards to who we consider to be a part of our community and what we consider to be our home. As we move from concrete loving relations to more inclusive and expansive (and yet also more abstract) objects of our love, the profundity of our love and the power it has over our actions can wane. And so, here we return to Judaism – the texts, rituals, and intentions found in the Jewish tradition are arranged as to help us grapple with these expansive notions of love. These words have shaped history, and yet the love found within communities remains fragmented and prone to stirring up conflict.

I return now to the question: “What is love?” It is something we all carry, and yet some of us never really know it. It is not merely a feeling nor a sentiment we ascribe upon something or someone; love is an attachment. All life depends upon the support of others. But human love is something qualitatively special amongst the animals. We are capable of using words to grapple with our relationships to others. Love is one such word; a word which carries such weight as to structure our internal models of our place in the world. And so, dear reader, how do you understand love? And moreover, how might you extend your love so widely as it motivates selflessness and compassionate concern for all other life?

Nice piece. How do you think about self-love? Your definition of love is big on how we relate to systems and objects outside the self, so I’m curious how love for the self fits into that framework, if at all. Would we be better off just calling self-love something else entirely?

First of all, I can't not read "dear reader" in the Lady Whistledown voice (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bs9r1UbmFAI&t=6s). Very comforting.

I think defining love may be useful in terms of understanding ourselves and our world, but I don't think that an individual can ever really define their love for other things, and certainly not their love for other people (or pets 🤷♀️). It's just something we feel, and we can examine its impact on ourselves and our society (ecology?) to try to glean some understanding of ~it~.