This post was released on the third day of Passover, an 8 day holiday in which Matzah is consumed instead of Chametz (wheat bread and other ancient grains). During passover, we recount the story of the Jews’ Exodus from Egypt, commemorating our freedom and honoring our past as strangers and slaves, bound in the land of Egypt.

Chag Pesach Sameach — Happy Passover!

This year, the first night of Passover fell on Earth Day. Whereas Passover is a holiday celebrating our freedom, we often imagine the environmentalism of Earth Day to entail constraints on freedom — using less energy, driving less, eating less meat, and so on. This Passover, we are left to wonder: How can we set ourselves free from the systems of oppression and greed, hate and fear; these systems which leave us paralyzed, unable to confront our dangerously broken economy and our illusions of freedom? How can we set each other free?

This Pesach, I’ve been thinking a lot about Matzah. The Bread of Affliction. A perennial symbol that, for eight days, reminds us that our freedom came with a cost – not just a cost imposed on the people of Egypt, but a cost we too must face. Throughout the year, we wait patiently for our bread to rise. We let our dough build up its gluten, we ensure our microbial partners have the time to multiply – our friendly yeast ensures our bread is soft and delicious.

But on Passover, we eat Matzah – flat and dry, bread that was denied its chance to rise. Passover is a holiday that honors our liberation – past and present. We tell the story of our Exodus from Egypt. Reminding ourselves that our freedom comes at a tremendous price – a cost with ramifications that reverberated across Egypt’s society and ecology, now echoing across the whole Earth.

Through a brief retelling of the story of the Exodus and some musings on the symbolism and deeper meaning of Passover, we will endeavor to better understand the nature of our freedom. As you read, try to keep this in mind – how do we lose our freedom? How do we get it back? How does our relationship to the World — the water, the Earth, and all of Life — teach us the reality of our freedom? What can we learn from Matzah?

When we tell the story of Passover, we remind ourselves of our roots. We must recall the memories and stories that have come to shape our history (and our myths).

A Passover Story

The story of the Jewish people, beginning patrilineally, with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (later to be named Israel), starts in Mesopotamia. Let’s set the stage.

The lands of Mesopotamia are naturally irrigated with an influx of nutrients that flow downstream each year with the seasonal floods, making continuous agriculture possible. In this part of the world rain — falling on distant mountains — is the source of all civilization. The great rivers of the Tigris and the Euphrates start in the mountains of Anatolia, and each spring, water would bring bounty to the floodplains where families, tribes, cults, and early bureaucracies competed and collaborated with each other, transforming watersheds and building vast networks of trade. But as the forests of the foothills were cleared for fuel and building materials, and climate changed; and as irrigation networks proliferated and plowing eroded the soil, social and ecological instability eventually led to polycrisis. It is said that Abraham’s father was a crafter of idols — and Abram recognized the falsity of the gods of Sumer. When ecological crisis led to social turmoil, Abram (later to be named Abraham) took his family West, abandoning the declining city of Ur and heading West. Eventually, Abraham came to the land of Canaan. In Canaan, without any large rivers, shifts in the weather and climatic change can lead agricultural and pastoral lifeways to ruin. Many years past, but soon drought struck. Famine followed. Abraham fled to Egypt, where news of bountiful harvests and full granaries led many stricken wanderers to seek refuge. He later returned to the land of Canaan, with the gifts and support from the Pharoah.

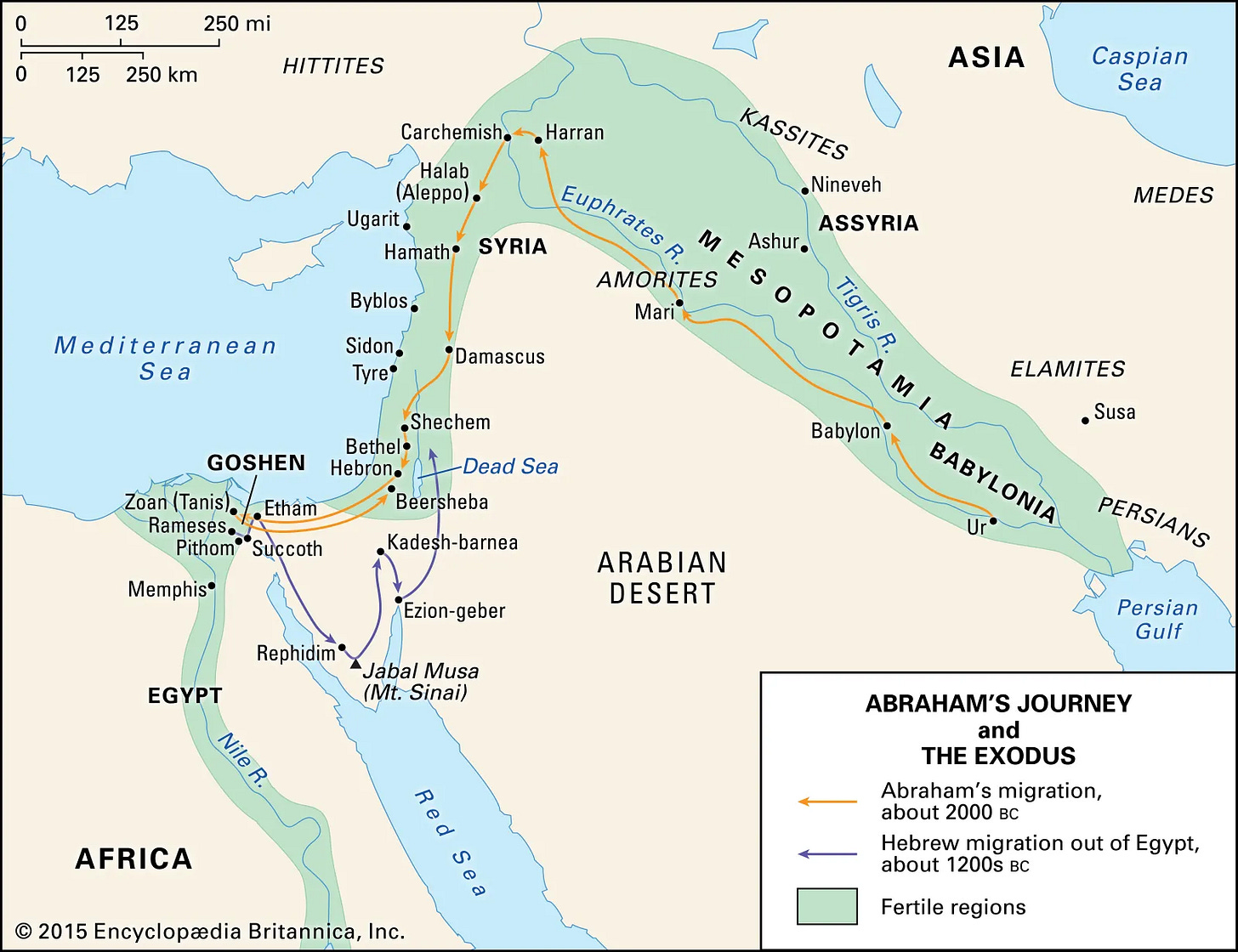

A map showing the journeys of the ancient Hebrews, including both the approximate path of Abraham’s journey, as described in the Book of Genesis, and that of the Hebrews in the book of Exodus. Map from Encyclopedia Britannica.

Generations passed, and Israel, son of Isaac, son of Abraham — with his many children — dwelled near the Mediterranean coast. It is said that the sons of Israel, out of envy, abandoned his favorite son, Joseph, leaving him to be taken into slavery. Joseph was eventually trafficked into Egypt, where he impressed the Pharaoh with his ability to interpret dreams.

One day, Pharaoh had a dream. He saw 7 fat cows be consumed by 7 sickly ones. Joseph saw this to mean that while the next 7 years would yield bountiful harvests, the following 7 would be struck by drought and misery. Trusting Joseph’s foresight, the Pharaoh ensured that the surplus from the 7 bountiful years was to be stored, ensuring the people of Egypt could survive coming drought.

Seven years of perfect weather were followed by seven years of drought. Jacob’s family heard news of Joseph’s success in Egypt. Year after year of poor harvests led them to seek aid in Joseph. While Joseph managed to ensure the Pharaoh's welcome, his family stayed in Egypt for many generations. Soon the family Israel lived as slaves.

I would like to pause here to remind us that the family of Jacob/Israel are said to be the forebears of the entire Jewish people. But in reality, with generations upon generations of people migrating and building families and communities all across the world, they are all our ancestors. Modern genetics teaches us that these people — assuming they really existed — are likely a part all our family trees, weaving nearly every person alive today into this legacy. We were all bound in Egypt. And yet, we all – including us Jews – likely had ancestors who acted to enslave us. Perhaps even Pharaoh himself.

As slaves in Egypt we may have had bread. But we did not have our dignity. We were beaten, we were exploited, we were resented, but we had our steadfast resolve. Our striving for freedom was not born out of free choice, but out of need: out of a desire to live a better life. G-d spoke through Moses and struck fear into Pharaoh's heart. And yet, even with plague after plague — transforming the Nile to blood, devastating the fields and cattle, burning and destroying its buildings, eclipsing the sun for 3 straight days (symbolizing the chief deity of Egypt abandoning these people) — leaving the people and landscape of Egypt in ruin, the Pharaoh would not back down.

It took the unthinkable — the death of the first born, the most beloved children in all of Egypt — for our freedom to be won. With Pharaoh’s heart broken and his spirit crushed, he finally permit the Israelites to leave. And so, in haste, we fled Egypt. Heading east with only our vital needs – including our bread, flat and dry, never given enough time to rise or be properly baked.

The rest of the story is miraculous. The Hebrews came forth out of Egypt with the help of G-d. Once they crossed the Red Sea, they were free from bondage. This image was produced as part of a collection of satellite imagery recreations of events from the Torah. Here we see the People Israel spilling forth towards freedom.

As a reform Jew and a student of history, I do not believe these events really occurred. But I do believe in the deeper symbolic truths of this story. To become free, we must open ourselves up to the reality of our situation. We must recognize that we are not infinitely free, but that each of our lives and actions are woven directly into the fabric of Nature. We must realize that our existence depends on our whole community, including the symbioses which make our place in the natural world possible. Freedom is hard and we must struggle to attain our freedom. We must work to align our desires and needs with the possibilities afforded to us by Nature. We must speak out and stand up to those who seek to keep us bound in their chains.

Some Musings on Matzah

Matzah is one way we commemorate our movement towards freedom. We remember the story of Moses and the Israelites because they remind us of our duty to strive towards freedom. We honor those who take steps towards freedom, even when those steps leave us dwelling in discomfort. Like Matzah, the movement towards freedom is not always given time to rise – and yet, we make do with what we have as we continue to strive towards our collective liberation.

We call Matzah “the bread of affliction”, yet it need not oppress or afflict us. We eat it to remind ourselves that to be truly free is to endeavor – hand in hand with our tools and our community, embraced by Nature as a whole – to move towards a better place. A place where no one is in chains. Where all can live the lives we yearn for. Where all life is sacred and we all dwell in peace. Passover reminds us that though we might imagine something better, it will take work, and occasional suffering, to get there. But it's worth it.

May we strive to limit suffering as we work together towards freedom and peace.

Hamotzi

A Prayer for Bread

When we eat matzah, we usually do not say a special blessing (aside from the seder on the first night of passover) – we say the exact same words we say when we eat bread. We say the “Motzi”, or rather “Hamotzi.” One literal translation for this prayer is as such:

Blessed are you, G-d

Majesty of the Universe,

Who brings forth bread from the Earth.

The translation of the word “Hamotzi” lies in the heart of this prayer: G-d who brings forth. It is no coincidence that Matzah and Motzi sound the same. G-d brings bread forth from the Earth just as G-d brought us forth from Egypt. In being brought forth, we are transformed. Just as we bring bread forth – growing and grinding wheat, mixing wheat and water and transforming these materials into something new, and finally, baking the dough into bread – we are brought forth in a dynamic and interweaving process of change. We live within these processes of Nature.

To be brought forth into freedom, we must organize and speak from a place of compassion, freedom, and Truth. We must be willing to change our ways, to eat food that doesn’t fit our ingrained standards. We must be willing to endure change, and to move together towards a better place.

The story of Passover, together with the symbolism of Matzah, reminds that freedom requires action. Action rooted in our desires, our dedication to one another, and the will to bring forth change.

At the end of the Passover story, the People of Israel find themselves on the Eastern shore of the Red Sea. G-d had just miraculously parted the Red Sea, ushering us out of bondage and into freedom. With a vast desert before us and infinite opportunities and dangers ahead, we danced.

Thank you for reading Jewish Ecology. This blog aims to build a participatory dialogue in which important ideas at the intersection of Judaism and ecology can help us root ourselves in the World. This blog is not just for Jews; I aim for these articles to be accessible and impactful for anyone that is interested in building up an understanding of the role that spirituality, philosophy, and/or ethics play in bringing about a more peaceful, ecological, and sustainable future for all People and the World.