Finding Community through Ecology

Community has always been the center of my Jewish identity. And yet, as an ecologist, I have come to know and study community as something far broader than narrow institutionalized groups.

In the modern world, there is a thin line between feeling a sense of belonging to the place, community or body in which you live, and a sense of utter alienation from one’s place in the world. For me and my recent ancestors, that line goes by the name of Judaism – and only through authentically addressing my inner Judaism have I found my own path towards feeling “at home” on my local landscapes, in my local communities, and in my own body. To me, Judaism is not primarily a religion, it is a community. Not an isolated community, nor an imagined community, but a network of familial, intellectual and lived relationships that empowers me to live each day to its fullest, to seek belonging everywhere I go, and with every step I take my Judaism penetrates deeper into my lived experience.

But what do I mean here by “Judaism”? Talking to both of my Jewish grandmothers, Judaism did not represent a rigid dogma or orthodoxy, and it is neither a set of laws we hold fast to nor is it a prescribed way of interpreting the traditions we maintain. To my parent’s parents, Judaism was a community where their kids could grow up and learn how to engage in a community – a community that although it maintains traditions distinct from those observed outside its margins, functions chiefly as a group in which each child can learn what it means to be a person first and a Jew second in the modern world. In this sense, Judaism transcends the typical boundaries held by “religions.” Judaism, as my parents, alongside my many Jewish teachers have taught me, is a way of living in the world. To be a Jew is to be an ethical person in the world. To be a Jew is to acknowledge one’s responsibility for the world. To be a Jew is to recognize one’s place in a Jewish community and to work towards making this community, and all communities we take part in, a more just, fair and loving place for the generations to come.

My Judaism came back to me after I had learned to view the world through an ecological and thoroughly humanistic perspective. This perspective grew out of my passion for engaging with the myriad of other lives I have come to recognize and worked to know. Listening to my ancestors talk about the culture they carried with them across the Atlantic and into this “new” land, I have since come to recognize the essential role that other-than-Jewish education plays within the development of an authentically Jewish consciousness. As my great grandfather said in a recorded interview I am forever grateful to have heard, “In our family the importance of an education far exceeded the importance of a full belly.” Education can never be strictly Jewish, and for the Jew, no education can be devoid of one’s Jewish context. To be a Jew is to hear the ethical call of one’s learning and to recognize the invaluable contribution each and every one of us can make by synthesizing the perspectives we hold into a broader perspective that all can appreciate. To be a Jew is to be a part of this community. A community of words and of stories, a community of knowledge and of values. To be a Jew is to participate throughout the course of one’s life in bettering the communities in which we live; the very same communities that we will leave behind for generations to come.

But grounding Judaism in the present depends upon recognizing that we don’t live in exclusively Jewish communities – nor should we aspire to. Every living being lives in a community. To live is to commune with one’s environment – and every living environment is full of other lives whom our actions will inevitably shape. As a Jewish ecologist, I recognize that for a community to exist, it does not need to be psychologically recognized as such. And yet, I also recognize that when we bring the communities in which we live into our full apprehension, the capacity we have to consciously and ethically engage with the others who live alongside us is infinitely larger.

Following my confirmation at age 16, my career as a scholar really began to take shape. Entangled within various academic institutions, I lost sight of my Jewish roots. And yet, as I began to extend my curiosity beyond the intersection of the evolution, life, water and history and towards more philosophical questions regarding the nature of the human mind and community, I returned to reconsider my personal history: my life has since its beginning been attached to various Jewish communities, and as I have grown, it is within Jewish communities that I came to know community as such.

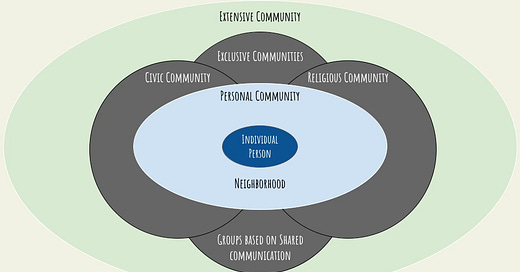

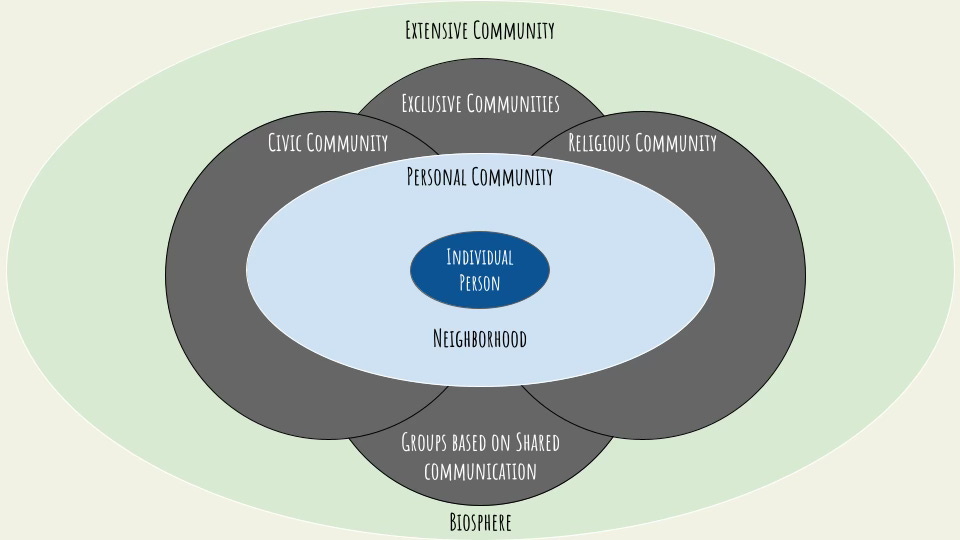

We all live in communities – whether or not we know it. It takes a village for a baby to make it to adulthood, and no person lives as an isolated individual. Furthermore, all of our ideas are learned. Whether through relationships based on trust and respect or through lived experience, the ideas we come to hold are directly connected to the communities in which we live and learn. These were the primary insights that led me to recognize the concept of a personal community. Each of us has one – it is composed of all the lived relationships which form us into the person we are and will become. But this is not what we think of when we consider communities as we know them. This sort of community I recognize as “exclusive communities.” For an exclusive community to exist, it must be upheld by an institution and continuously reconstituted through various rituals, relationships and responsibilities. Critically, exclusive communities depend on individuals being able to cognitively apprehend themselves as either within or outside the community in question. While in principle an exclusive community can exist without tribalistic in-group/out-group divisions and identification amongst people, the reality of such communities is as groups of humans amongst whom individuals are collectively understood through internally constituted social roles, rules, and collective identity. These sorts of relationships always lead particular individuals to be elevated while others are denigrated, and throughout the whole unfolding act of participation, individuals are forever left negotiating their personal identity in relation to the group. The tension between lived personal communities and institutionalized exclusive communities continued to create division where none need to be. My exploration of philosophical underpinnings of community has led me to recognize that social ecology at its heart is the Judaism rendered into science – coming to know our personal relationship with G-d through learning to love one’s neighbor.

A community does not need to be psychologically understood as such for a communion between beings to exist. When we take our time to commune with others, we find community where we did not recognize it before. When we stare our pets in the eyes, when we take the time to embrace a tree, when we plant a seed, tend to it and watch as it germinates and blooms, we commune with others; in some small way, we make each other's lives possible. The same can be said with every breath we take. But if we are to give gratitude for our past and continued sustenance, only by considering the entire world can we properly give gratitude for beings that make our lives possible each and every day. This insight led me to recognize a third sort of community – a community which might necessarily only be grasped when we consider the whole of space and time. Each of our personal communities is a subset of this community, and when we take the time to grasp the truth of our dependence on the whole community of the cosmos, our personal communities become extensive, reaching as far as our minds can take us. This community – which ecologists have dubbed “the biosphere” – really extends beyond the Earth, beyond the limits of our mental apprehension and our possibilities for knowledge. Each day, the world is kept alive through a continuous interaction between the sun and the Earth. And yet, the building blocks which construct us and everything we could possibly use have their origins back to the dawn of time. When we try to apprehend the community in which we live as such – as an extensive community through which all comes into being – our scientific knowledge approaches its limits and our profound sense of wonder approaches G-d.

Adding nuance to our comprehension of community can help us deepen the relationships within our congregations and between human and more-than-human ecosystems.

Within scientific ecology, the individual organism is always located within a community. Two relevant scales of this community exist in this space: the neighborhood and the biosphere. The ecological neighborhood is a territory in which direct relationships shape a developing organism. The size of this neighborhood varies from species to species, organism to organism, and across the lifespan of any particular organism. The size of an organism’s neighborhood depends upon the particulars of its ecological niche, as well as its physical size, and the particular range and scope of its habitat. When we go from considering the neighborhood to considering the local community, we center the direct relationships between organisms, effectively moving towards a more generalizable definition of the “personal” community. The biosphere on the other hand incorporates all the indirect relationships within which an organism develops, providing an ecological understanding of the extensive community as it connects us to the planet we all share.

To me, to be a Jew is to be concerned with the Whole, and to live each day working towards the liberation of all living things. Thus, my community philosophy is at the heart of my Jewish ecology. To build a world beyond tribalism and parochial tradition is to recognize that Judaism is a living religion – we need not stay trapped in the proscriptions of past millenia nor the follies of popular Jewish Politics. Rather, we must reckon within ourselves and across our communities to separate Judaism of nationalism, dogmatism and trauma. For the Jewish people to truly live, we must find new methods towards finding community – and feeling at home – wherever we live. Community exists wherever one takes the time to connect with other beings. To be a Jew is to hear the call of the other – even if this call is beyond words – and to respond to this call with the same moral imperative we owe all our relatives. For we are all related, and our future ancestors are depending on us.

Thank you for reaching the end of this article. Please leave a comment sharing any practices or techniques you or your communities have used to deepen your connections with one another or with the more-than-human world, or your thoughts on this article!

I often find that Shabbat is the Jewish practice that helps me deepen my connections to my "neighborhood" and to the larger more-than-human ecosystem. Specifically, Shabbat dinner and the practice of actively resting (which is often accompanied by contemplating) are good for this.

Jordan,

I am impressed by your writing and intellect. I was also very touched by many parts of this piece. One of my favorite lines was, “To live is to commune with one’s environment – and every living environment is full of other lives whom our actions will inevitably shape. “ I look forward to reading and learning more from you.

All my best,

Kristi