Created in the Image of G-d

Rediscovering an Ancient Idea through Religion, Philosophy, and Ecology

Know that this Universe, in its entirety, is nothing else but one individual being… The variety of its substances…is like the variety of the substances of a human being … One individual, consisting of various solid substances, such as flesh, bones, sinews, of various humours, and of various spiritual elements.

- Rabbi Moses Maimonides, Guide for the Perplexed, 1190

In the first chapters of the Torah, we learn that each human being is made b’tzelem Elohim — in the image of G-d. We first see this phrase early in the book of Genesis, as the story of the creation of the first human beings is recounted, even before we hear that G-d created humankind from clay and breathed into us the breath of life.

In this article, we will explore the spiritual and ecological truth that lies within this idea – and in the process, I hope to show how the divine spark within us all, our neshama, transcends the boundaries we imagine to separate body from mind, men from women, Jews from gentiles, and human from non-human.

If we are to understand this idea — and the heart of Judaism more broadly — we will first need to appreciate the broader landscape in which these spiritual ideas first entered dialogue with Greek philosophy. Prior to this encounter, Judaism was impossible to separate from the spiritual, ecological, and theocratic ideologies held by various individuals within the post-exilic Jewish communities. Yet, as Jews engaged in increasingly complex dialogues with various other perspectives — especially in the Hellenistic world — the unique insights of the Jewish tradition became ever more clear.

According to the Torah, the first man, Adam, was made from dust and clay, earth: adamah. It is no coincidence that these two words have the same root. Humankind has been sculpted by the forces of the Earth; we are a microcosm of all the matter and energy that brought the Earth into existence. No matter the sex, culture, or way of life, all human life is intrinsically linked and inseparable from the Earth. Human life and the wider world we live in are two parts of an interdependent whole. This idea lies at the heart of the Jewish creation narrative, and at the core of our responsibility to it all.

This idea has since gone on to shape how philosophers understand the human place in the cosmos. But only after exile and diaspora, in cross-cultural dialogue would it come to shape the whole of “western” philosophy.

Philo of Alexandria — a diasporic Jew living in the academic center of Greek civilization in Egypt— is perhaps the first Jew to work towards a synthesis of the philosophical schools of the Greeks with the traditions and beliefs of the Jewish people. It is here, in and around the turn of the millennium (20 BCE to 50 CE) that Judaism made its most severe impression in the history of human thought. Synthesizing the G-d of the Torah, who brought about the world by speaking creation into existence, with the Greek understanding of the Logos — translated literally as the the Word and understood roughly as the coherent rationality which orders the cosmos and binds it together as a whole — Philo paved the way by which “western” philosophy would approach absolute Truth for millennia. Without him, a deity who both spoke the cosmos into existence and still acted in human history may not have been compatible with Greek ideas on the relation between gods and the cosmos.

To Philo, the human body itself is not an image of G-d. Rather, he saw the human soul as made in accordance with G-d’s Logos: our rational mind. This is what he understands G-d to have breathed into humankind. It alone is our divine spark. In essence, Philo connects the ruach chai (breath of life), with the neshama (thinking spirit), but does so by separating mind from the body – leaving the nefesh (physical soul/living body) separated from the holiness G-d bestowed upon us.

It took an esoteric leap — a dramatic fusion of Jewish, Greek, and Egyptian occult belief — for the notion that our bodies are made in G-d’s image to enter popular religious thought. Ironically though, it was not Philo who made this leap, but an ancient and strange figure: Hermes Trismegistus.

“Hermes the Thrice Great”, a syncretic character entwining the Greek god of travelers and the Egyptian god of knowledge, Thoth, is given credit for writing a compendium of esoteric texts, which first emerged in the late first century CE. It is hotly disputed who this “man” actually was, but it has long been a popular belief — arising amongst cosmopolitan Jews and gentiles in the Hellenized world — that he was either a contemporary or teacher of Moses. While Hermeticism, as this syncretic body of esoteric thought became known, had its most profound impact on various occult mystical traditions, and not Judaism, it was undeniably inspired in part by ancient Jewish ideas.

Hermeticism goes beyond Philo, revealing the human body itself to be a reflection of the universe, an image of G-d. From humankind’s creation in the divine image to G-d’s living presence in the world, we can draw a line to perhaps the most famous phrase found in the revered Hermetic text, the Emerald Tablet: “As above, so Below”.

This single sentence reveals a deep insight into the philosophies and spiritual beliefs carried by numerous sages and ancient worldviews. The human, below, and the cosmos, above, are parallel images of one another: interconnected, intertwined, and inseparably interdependent. The human body can be a microcosm of the universe: all of the forces that move through the cosmos also move through the human body. We cannot understand our world unless we can understand ourselves, nor can we understand ourselves unless we understand the world. Each of us is made in the image of G-d, and through our engagement with our bodies, minds, communities, and the wider cosmos, we can understand the nature of our existence.

Moving towards the present scientific worldview, I believe that Spinoza — the infamous 17th century Jewish philosopher of Ethics and G-d/Nature — can shed light on how we might reckon with this pre-modern wisdom in modern terms. To Spinoza, G-d is an infinite substance with infinite attributes, including thought (conscious reason) and extension (physical existence). Each of these distinct attributes themselves are infinite, allowing us to comprehend the whole of Nature through their existence.

[Spinoza] designates the number of the attributes of the divine substance as infinite. However, he gives names to only two of these, "extension" and "thought" — in other words, the cosmos and the spirit… for even the spirit is only one of the angelic forms, so to speak, in which God manifests Himself”

- Martin Buber, “The Eclipse of God”, 1952

I now want to problematize the notions of “above” and “below”. In Spinoza’s time, it may have been fashionable to see the mind as “above” the “body” – yet for Spinoza, mind cannot steer body, nor body mind. All of the actions of the body can be understood through the happenings and interactions of the extended cosmos. All of the actions of the mind can be understood through the happenings and interactions of the thinking cosmos. Yet still, while these attributes are distinct, they parallel one another – as above, so below. If all this seems strange to you, (could a body really paint a masterpiece totally independent of the mind?), I’ll leave you with Spinoza’s rebuttal: “Nobody knows what a body can do.”

There is another “above” and “below” in the works of Spinoza, which bears significance for our purposes. This ladder — ranging from from the parts that make up our bodies to the whole in which our body is merely a part — is perhaps best understood through his explanation of the relationship between particular bodies and the infinite body we might call the cosmos — what he calls “The Face of the Whole Universe.” So what does this relationship actually look like?

Early in the second book of his Ethics, Spinoza writes about the composite nature of complex bodies:

“When a number of bodies of the same or different magnitude form close contact with one another…these bodies are said to be united with one another and all together form one body or individual thing which is distinguished from other things through this union of bodies.”

And further he writes:

“Now if we go on to conceive a third kind of individual thing composed of this second kind, we shall find that it can be affected in many other ways without any change in its form. If we thus continue to infinity, we shall readily conceive the whole of Nature as one individual whose parts — that is, all the constituent bodies— vary in infinite ways without any change in the individual as a whole.”

This is the same construction procedure by which modern science might understand the integration of body and mind into a self; or perhaps by which Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism) understands the Oneness of Creation.

Through all this, Spinoza sketches out a physical picture regarding the integrated structure of nature. Science now understands this to range across orders of scale in space and time as ranging from the scope of particle physics and chemistry (particles and atoms, molecules and proteins), through the scales of biology (from small biomolecules to RNA and DNA, up through cells, tissues, organs and organisms) and all the way to the ecological and cosmological domains.

This is the physical map which modern science has left us to imagine our place in the cosmos. Spinoza thinks it might be useful for imagining the embodiment of the natural world, and our place in it. Does it adequately help us understand the powers and forces which integrates us into the universe? Can it help us see the face of the whole universe? Can we use it to approach the notion of the full embodiment of G-d (or Nature)?

I don’t think so. Modern science, as a social establishment and collective endeavor is still ill-equipped to fully comprehend the evolving complexity of nature and the cosmos. Perhaps though, by bridging the gaps in our Science, we might still come to appreciate and grasp the natural intelligibility and brilliance of the whole universe. To do this though, we would need to identify those gaps, and integrate our understanding of the cosmos with our whole understanding of life, humankind, and our collective endeavor towards ever greater love and liberation.

The modern conceptual map of the nested nature of our of the cosmos. Yellow triangles denote the primary scales by which modern science has significantly transformed our collective understanding of our world in the cosmos. The blue triangle indicates the region in which contemporary ecology may further our greater understanding of Nature and our place here.

Modern science has excelled in transforming our understanding of our place in the cosmos – no longer do we imagine that the universe was made for us, nor that the Earth lies at the center of it all. Through telescopes and particle accelerators, microscopes and breakthroughs in genetic research, we now often see humankind as an infinitesimally insignificant part of the cosmos. We are but a single branch of the tree of life, on a remote planet orbiting an average star in a rather normal galaxy. Yet merely by acknowledging your ability to hear these ideas — from my brain to yours through a complex network of technology — and to struggle with them as they really exist in our understanding, we must realize that we truly are special. Through further research in human ecology, moving from human consciousness and technology, to our responsibility here in the Anthropocene, we might bridge the gap from organisms and ecosystems, developing a deeper understanding of the nature of life and cosmos in the process

Let us now return to the teaching at the heart of this essay: We are all made in the image of G-d.

Like G-d, we are composed of a nigh infinite number of bodies, each made up of bodies in bodies in bodies. And yet, unlike G-d, we are finite, delimited in space, time, bound in a particular web of relations to others. Let us then look “downward” and “upward” in these scales, so we can appreciate the complex living beings we are, and in which we are a part.

When we eat, we feed our cells. But we also feed our microbiome, the trillions of bacteria and other organisms that live in us and on us. We cannot separate these microbial inhabitants from ourselves, as without them, we would not be ourselves, nor could our bodies continue to live.

We get our food from the wider world. When we thank G-d for our meal, we ought to be thanking the people who made this food, but also the water and soil, the sun and the sunlight which gives warmth and energy to us all, the seeds and microbes which fill our food with the nutrients we need. Looking “up” in this way, we can see the extensive community in which we are a part. A community which unites us with the world and our world with the wider cosmos.

Hopefully now you can see how — from microbes to humans to ecosystems to the cosmos — we reflect a deep biological truth: wholes emerge from complex interactions, the forces which bind communities are at play throughout it all.

The human body has emerged into the cosmos across the long arc of evolution: iterating across time in constant interaction with its wider place in communities and ecosystems. Human consciousness too has arisen in this web of relations. Yet, when it comes to understanding the miracle of human life, we cannot solely look at how “higher” levels of complexity arise from “lower” ones.

Humankind has thrived because of our ability to abstract general principles from particular experiences. Our knowledge of the cosmos doesn’t solely emerge from “below”, but also emanates from “above” – we come to a deeper understanding of nature through perceiving the interconnectedness in all things. Sky and stars, rain and growth, life and death; we come to understand the world through experiencing the unity of life and cosmos.

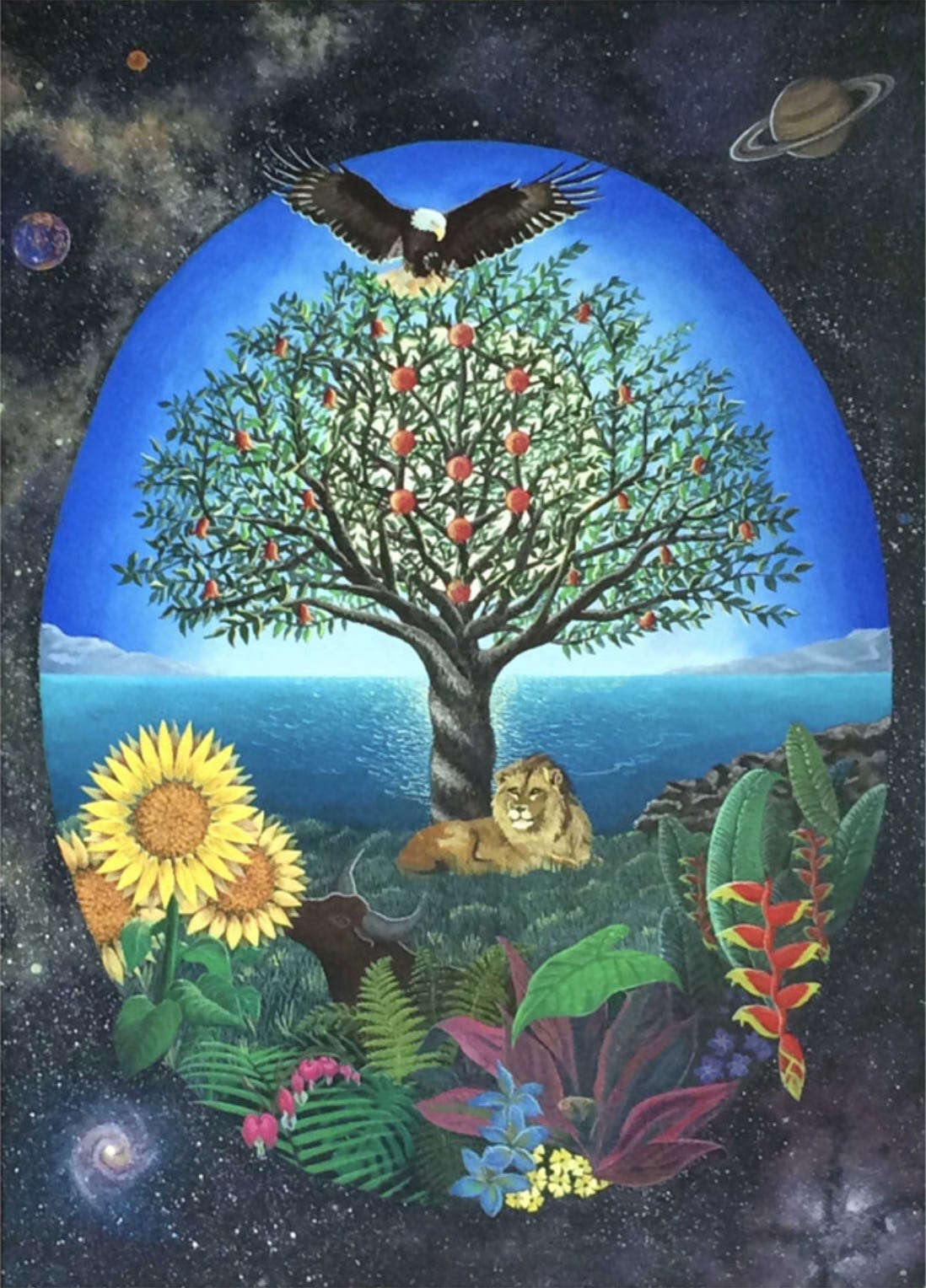

In her beautiful painting “Vision”, Bonnie L. Sachs illustrates the interconnectedness between life and the cosmos. In the center of the tree’s canopy, the Kabbalistic Tree of Life is depicted, revealing the fractal-like patterning of the divine: arising in every twig and branch, in every organism and ecosystem, through the sky and Earth, and across the whole cosmos.

In the struggle to understand our place in the cosmos, we come to understand the complexity that lies “above” us, infinitely extending across space and time. Humankind exists at the nexus of mind and body, abstract and particular: between an inexorable concern for the present and a limitless care for the past and future, self and other. This is the miracle of humankind: we are forever stuck deciphering the meaning of our unique place in our ecosystem, staring out at the landscape and up towards the stars. Only through knowing our place here, and appreciating our ability to shape our ecosystems and to create new tools and relationships do we find a sense of care, guiding us to cultivate a sense of responsibility for all of creation. This leads us back to our divine spark, the infinite capacity of love which lies within us.

We all carry the image of G-d within us. We are an extensive community, home to trillions of inhabitants who rely on us to live well. And we live within an extensive community, in which we rely on an unknowably large number of people, places, and others to sustain our existence. With this insight, we realize that all organisms are microcosms of the macrocosmic whole we call G-d. As above, so below: we are not separate from the G-d, we are not separate from our bodies, all is One.

If the image of God is an image of the diversity of life, then God’s image is diminished every time human beings cause another extinction.

- Rabbi David Seidenberg, Kabbalah and Ecology, 2015

Thank you for reading Jewish Ecology. This blog aims to build a participatory dialogue in which important ideas at the intersection of Judaism and ecology can help us root ourselves in the World. This blog is not just for Jews; I aim for these articles to be accessible and impactful for anyone that is interested in building up an understanding of the role that spirituality, philosophy, and/or ethics play in bringing about a more peaceful, ecological, and sustainable future for all People and the whole of Nature. If you can think of someone who might enjoy these articles, please consider sharing this blog!