This article was started on Yom Kippur, and completing in the days leading up to Sukkot — From the Day of Atonement to our Harvest Festival of Huts. This marks the start of the Jewish ritual year, full of new beginnings: a return to right relation with our neighbors, with our climate, and with the Earth; we begin the Torah anew, tellings once again our stories from the first moment of Creation. Together, we wash away our sins, and together we harvest our fields. Yom Kuppur and Sukkot serves to reminds us that our wellbeing — and that of all life — are forever interlinked. Together we must work to build a life of love. From Yom Kippur to Sukkot, we are reminded that only together cane we bring ourselves a year of us abundant rainfall, plenty, and peace.

On Yom Kippur we atone for our wrong actions. All the harm we have done: to ourselves, to others, to the Earth, to all our neighbors-past, present and future.

We repent for ourselves through the united voice of our community, grounding ourselves together in knowing that we are responsible for our life here. The sin of the one is the sin of the many; the sins of the many are the sins of the one. We take collective responsibility for enabling harm, and renew our vows for working for the wellbeing of our shared home.

When we take responsibility for our place, we do so as a human being, coming clean with the Divine as part of one’s community. Each year, we share this moment together because it sets our whole community on the course for doing good unto one another, as a community: both within and beyond the limits of the congregation. We recommit ourselves to justice and freedom, love and compassion, committing ourselves to do better in the year to come. Our ever-renewed dedication to the universal value of life and the oneness of G-d has led many Jews to expand our collective empathy and broader concern for each other — moving beyond just all Yisrael, but to encompass a responsibility for all life. But perhaps, this is just the natural course for our “struggle with G-d”.

The tension within this movement toward expansive universality has increasingly come to define modern Jews’ relationship to the wider world. This is most clear in the case of Jewish tribalism — an insular group identity that has mutated from its likely origins in the inter-tribal confederation of the 13 tribes of Israel, into a single pan-Jewish tribe, which tries to include all Jews yet often fails to seriously interrogate the dangers of tribalism. These tensions have intensified as Jews have had to struggle with our relationship to the state of Israel, which proclaims itself as a “Jewish state” yet often fails to live up to our ethical values. Within the tension between universal and particular, Jews have diverged, with common disagreements springing up between differences in traditional and adaptive rituals, orthodox and reform traditions, nationalisms, assimilation, and Jewish universalism. Taking responsibility for all of humanity is understanding that we are complicit in the harmful relations that are endangering the stability of our biosphere.

When we repent for the sins of hatred, violence, genocide, and the theft of homes, we commit ourselves to liberation and justice for all. It is critical that we recognize the violence we are most personally implicated in — the violence embodied in our relation to the land and nation we live in, in the clothes we wear, the food we eat, the commodities we buy, the fossil fuels we burn, all that we waste and destroy — but we must also recognize the systemic violence that we have inherited, that we might perpetuate. We must repent not just for the harm we are aware we have committed, but also for the damages we fail to see: all that we have done nothing to prevent. Repentance leads us to Teshuvah—it guides us in our everlasting return to our highest selves. This means that we must open our minds, see the world in all the ways we relate to our communities, and act in a way that honors our bodies and communities, our ecological and cultural diversity, our world and the cosmos as One. Returning to the Great Mystery of life, the universe, and everything, and realizing G-d’s creation continues in our every breath, renewed every day, every week, every year; Creation eternal. We find gratitude, love, and yearn for freedom. Throughout the year to come, we will tell our stories again, we will embody the liberation of our people from Egypt, and we will work through love for the liberation of all people. This is how we build this world with love. Together.

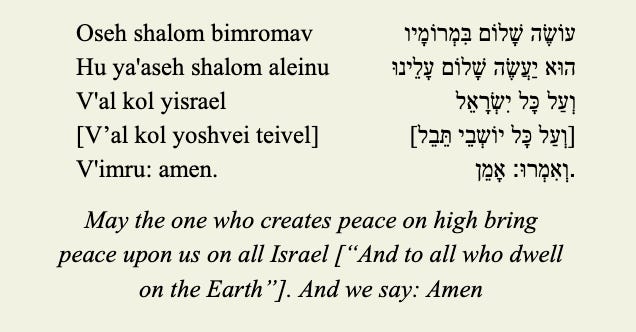

Whenever Jews come together to pray, we mourn. We call each other to prayer, we proclaim G-d’s oneness, full of love. And we declare G-d’s magnificence: this awesome life, this wondrous Earth! And together, we mourn. The Mourners’ Kaddish (from the Hebrew word for holy) is the same Kaddish we say as a transition prayer, moving our service liturgically forward between, for example, our morning blessings, and our Amidah (Standing) prayer. At the end of the Kaddish, we traditionally say the following Aramaic words, which have since become numerous closing songs to services:

Many Jews today add this additional line “V’al kol yoshvei teivel” saying, “And [may peace be brought down] to all who dwell on the Earth.” This step — towards universalizing our dedication to peace and proclaiming our responsibility for the wellbeing of our entire community, extending out from us through a single web of relations, weaving life together in community with the land and water of our one Earth — defines a large movement among Jews to reject tribalism, recognizing instead that our future is interwoven with the future of all life, all peoples, all species. May we start this Jewish year with a sense of love and responsibility for our place in the world, and may we build community in peace for the health and liberation of all life.

From this point, the Jewish year turns toward Sukkot, the fall harvest festival celebrated in community under the open sky. On Sukkot we build sukkahs, open-roofed huts built from all sorts of natural materials, most often sticks and palm-fronds. The roof must be made of something grown from the ground, which has since been harvested. The stars must peak through the roof, allowing us to remember that the lines between inside and out are not opaque, but constructed, traversable. During Sukkot, we live in our Sukkahs, and for seven days we build community with permeable walls between us, knowing that we are part of our one great community.

Painting of a Sukkah, by Anya Starr of Dawnstar Studios

The holiday of Sukkot lasts seven days, and throughout it we are instructed to dwell in our sukkah, eating meals and sleeping under the stars. Sukkah means hut, or booth, and Sukkot means huts, or booths. This is a holiday honoring our holy community; we are not supposed to build our sukkah alone, but alongside others. Together we harvest the fruits of our labor, and together we renew our holy community. Through the harvest, we remember that the work necessary for our lives can only be completed together, and together we must strive towards harmony. We welcome each other into our dwellings, we share meals, and we live merrily together. This is why Yom Kippur precedes Sukkot. By coming together and making amends for the damages done in the past year, we prepare ourselves to be together in joy and compassion. By washing away our sins as a collective, we ensure that the year to come will be a bountiful one, a year of peace, love, and plenty.

As we move into this new year, another year in which most of us are so dissociated from the agricultural labors and extensive community that makes our life possible, another year in which Jewish identity is made alien to Muslim identity, and in which Christian-dominated governments seek to demonize the Other in pursuit of an isolated sense of security, we must pledge ourselves to build towards mutual belonging, towards a rooted responsibility for our home. To build a community together, and to do so in harmony with the Earth, requires that we open our hearts to our neighbors, opening our eyes and ears to really grapple with what they have to say. We live in a world of many stories. Of many truths. If we are to build this world together with love, we must find common ground in the gray space between the apparent binaries of white and black. We must realize that we all have far more in common with other life than we do with the political forces that guide people to hate, kill, and destroy. We must work towards building loving relations with our neighbors, maintaining connections and constructing bridges across which real dialogue, learning, and peace can flow.

May this year be a year of community-building, peace-making, and justice; may this year be one of life and liberation for all who dwell here on the Earth.

Thank you for joining me on the journey through Jewish Ecology. This blog aims to build a participatory dialogue in which important ideas at the intersection of Judaism and ecology can help us root ourselves in the World. This blog is not just for Jews; I aim for these articles to be accessible and impactful for anyone that is interested in building up an understanding of the role that spirituality, philosophy, and ethics play in bringing about a more peaceful, ecological, and sustainable future for all People and the World. If you can think of someone who might enjoy these articles, please consider sharing this blog!

Sources:

Anya Starr. Sukkah. Painting. Dawnstar Studios. Webpage.

Thank you!

I was raised Christian in the United States. I have struggled with so many aspects of what I was taught. Your writings resonate a lot, and provide a perspective that feels so much more genuine.

I don't think I am Jewish (that's something your parents would know and tell you, right?). But I really like the sound of a lot of the traditions, rituals, and community life that is attached to Judaism. How much of that am I welcome to engage in without committing cultural appropriation or disrespect?