Bringing Niche Construction into View

Academic science has a history of narrow research -- yet new trends in ecology and the philosophy of biology are making way for an integrative synthesis. We start our review of this research here.

I had planned to put out a much more expansive article this week as we delve into the intricate relationship between human consciousness, culture, ecology, and human niche construction. Through a synthesis of published and peer-reviewed articles, these topics can be grounded within an integrated scientific approach to Life. I intend to publish this article in the coming weeks, but in the meantime, I want to return to two articles that had a formative impact on how I think about philosophy, biology, and the human niche. For science-dense posts like this one (with more to come), I will try to include links to the full papers at the bottom of the article (although if articles are not open source, I may just link the abstract). As I can’t go over research articles in their complete depth and nuance, if what you read here piques your interest, I encourage you to explore them further (and they are linked at the bottom of the article). This article stands as the second piece of a series on the human niche. If you haven’t read the first post (introducing this concept), I encourage you to check it out here. For now, I hope you enjoy as we review some of the foundational interdisciplinary research that set the stage for our collaborative project: Jewish Ecology.

An integrative approach to the human niche provides a conceptual framework to holistically consider the human place on the Earth. The human niche brings into view the complexities that connect the development of our individual minds and bodies to the broader physical and sociocultural matrix in which we are raised. But before I can delve into describing and presenting the numerous facets that constitute our niche, I want to present two key scientific papers – both of which played a foundational role in helping me understand the dynamic niche construction that coincided with the evolution of humankind. In this article, I will lay out two approaches to niche construction: reciprocal causation (as presented in a 2021 article in the journal Biology & Philosophy) and triadic niche construction (presented in 2012 in a special edition of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Review of Human brain evolution). Through these two entwined philosophical/scientific approaches to conceptualizing the interactive dynamics through which organisms evolve, I want to give you a window into the processes which brought me to my current understanding of evolution (which, for those familiar, is nearly in line with the extended evolutionary synthesis). By exploring these interlocking approaches, I aim to provide insight into the journey that has shaped my understanding of human ecology and evolution – bringing us ever closer to unraveling the complexities of the human niche.

First, a brief note on context. In late 2019, I was an undergraduate student looking for a research lab to participate in. I had recently become aware of my interest for plant diversity and my passion for ecology, and I lucked out: the university in which I was studying had several plant research labs, but none were very competitive (unlike the bio-medical research labs). In Fall 2019, I joined a plant community ecology lab. While I was new to community ecology, this lab centered plant functional traits (quantifiably measurable features of plants that most plants have, which have some bearing on the organism’s niche), analyzing how a multi-trait approach allows us to comprehend and predict the environmental tolerance, competitive ability, fitness, and persistence of a species in a community. Most intriguingly, this lab helped me understand how an organism and its niche interrelate, allowing us to understand how a plant’s structure and function fit within its niche, driving its ability to exclude or coexist within a particular plant community. I have since graduated with a BS in ecology and an MS in biology, but through this journey, and until today (ending in June of this year) I have remained involved and deeply interested in the work of this lab.

Reciprocal Causation

In 2021, while still an undergraduate, the professor running this lab shared a recently published article written by three philosophers (of biology), titled “ Unknotting reciprocal causation between organism and environment.” In this article, the authors Jan Baedke, Alejandro Fábregas-Tejeda, and Guido I. Prieto seek to show how organisms and environments reciprocally shape each other. They show this by building up a model for “reciprocal causation,” a framework through which organisms shape their environment precisely as the environment shapes its organism – and although these entities remain distinct, their mutual impact on one another involves both accommodating the other. Before getting deeper into the weeds of this paper, I think it is important to note that this form of causal relationship occurs wherever two beings mutually affect one another – for instance, in a genuine dialogue (a conversation in which all parties work to actually listen and respond to one another), the dialectical unfolding of understanding is inherently caused in a reciprocal, co-constructed fashion. In all cases where existence necessitates mutual accommodation – such as when a plant's roots recruit specific microbial species into the adjacent soil and the rhizosphere (the root microbiome), the soil is shaped in the process; meanwhile, the broader soil environment, including its microbial constituents, influence which species and challenges the plant encounters. Here, causation occurs in a reciprocal fashion: all shape all, none are left unchanged.

To lay out the details of reciprocal causation, Baedke and her colleagues first lay out a cybernetic schema showing the physical connections and structural coupling between organisms and their environment. By showing how organisms interactively perceive and affect their environment, this approach centers how organism-niche relationships depend on an organism’s ability to respond and acclimate to their environment, behaving to modify themselves and their niche.

Figure 1 from Baedke et al. 2021 showing the cybernetic coupling between organism and environment. The organs are coupled through the organism’s “neural” structures, whereas the carriers are coupled through the body, behavior and objects afforded to it by the environment.

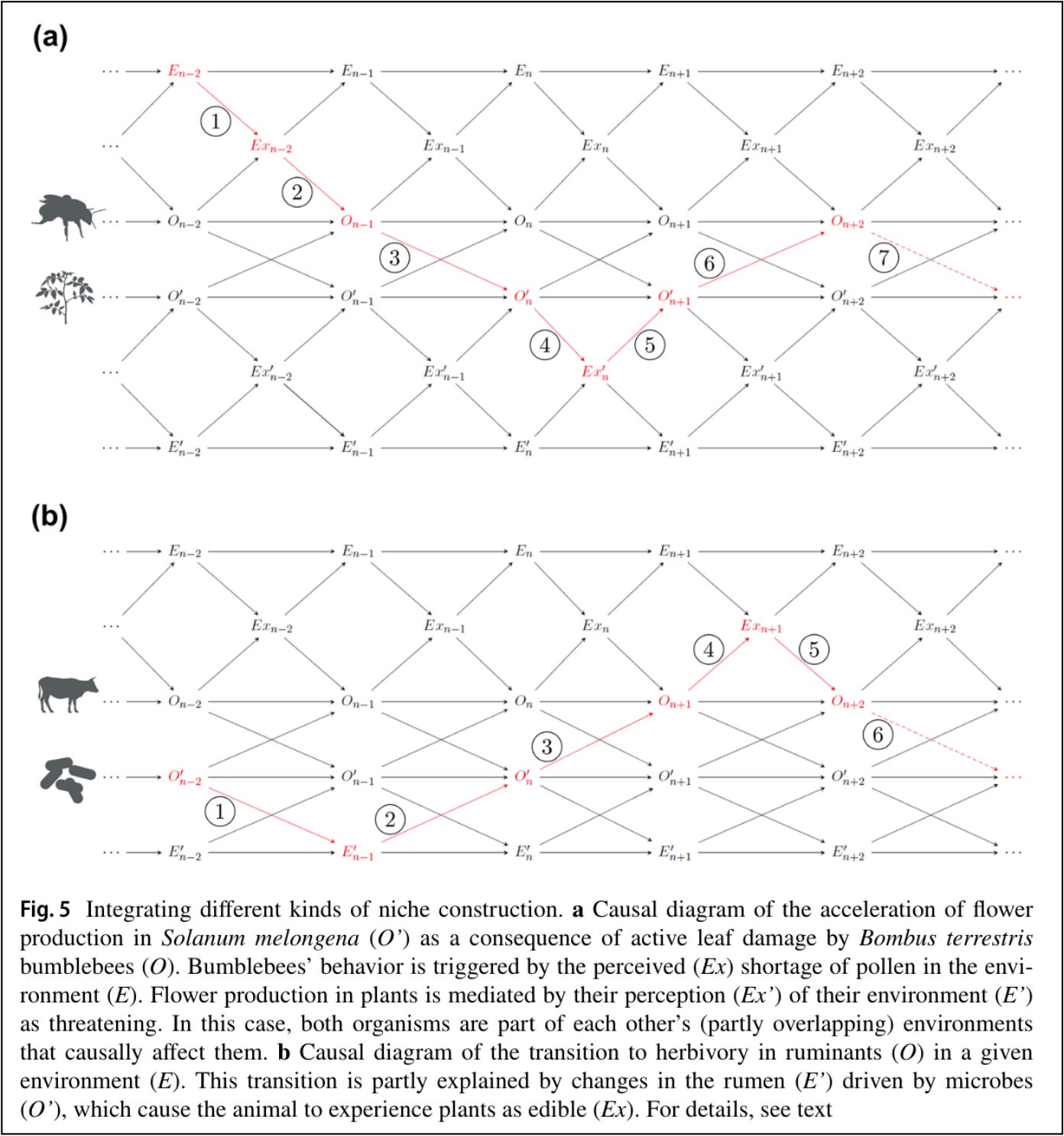

Reciprocal causation is complex — driving change through mutual coexistence — but through it, we can come to understand the interconnectedness that has formed our World. In this model, change emerges through the entanglement of organisms within communities and with their shared environment. Importantly, this ecological entwinement occurs on multiple levels, each with implications for niche construction. First, organisms come to know their environment (E) through their experience – this becomes known as Ex, the experiential environment. Each organism (denoted O) is in constant relationship with its own environment, unfolding over time (with the present labeled as En and On, and the past and future denoted in discrete time n-2, n-1, n+1, n+2).

Figure 5 from Baedke et al. 2021 showing how (a) the reciprocally-causal interaction between a bumblebee and a nightshade plant: before the present moment (n), a pollen shortage in the environment is perceived by the bumblebee, leading the bee to damage the nightshade’s leaves; active leaf damage then stimulates increased flower production. In the lower figure (b) we see how ruminant animals’ diet changes in direct relationship to the bacteria that inhabit their gut (their microbiome), which leads the ruminant to experience plants as edible.

Through reciprocal causation, the connections between organisms and environment are shown as mutually constructive – organisms acclimate to their environment, but organisms also shape their environment. In their paper, Baedke, Fábregas-Tejeda, and Prieto effectively show how this form of causation underlies niche construction – with organisms shaping and being shaped by not just their environment, but also their microbiomes, and their broader living context.

Triadic Niche Construction

I now want to turn to a scientific review article I came across in 2022, coming to my attention as I was initially beginning to think about the interaction between human ecology, evolution, development and culture. Published in 2012 by two researchers at the RIKEN Brain Science Institute in Japan, this article caught my attention because it advanced a reciprocally causal framework for the evolution of the human mind. Titled “Triadic (ecological, neural, cognitive) niche construction: a scenario of human brain evolution extrapolating tool use and language from the control of reaching actions”, this article advances a perspective on the evolution of the human mind, rooted in our upright stature, our tool use, and the changing neural architecture that enables our cognition.

In their paper, Atsushi Iriki and Miki Taoka present “triadic” niche construction – a reciprocal framework in which changes in the neural niche, the cognitive niche, and the ecological niche interact to shape the evolution of one another. While I intend to dive deeper into the cognitive niche in my next article, we must gain a cursory understanding of these three domains if we are to understand how and why this multi-level niche construction framework is valuable to thinking about human ecology and cultural evolution.

Let’s start by covering the three distinct niches (or perhaps the three distinct facets of a single niche) covered by Iriki and Taoka. While I described the niche in my last article, the framing I took approaches the niche as a single holistic system. Iriki and Taoka postulate that the niche can be subdivided into multiple distinct structures – ecological niche, which is external to the organism and is comprised of all the various resources needed to support one’s life; the neural niche, which is composed of the interconnected cells through which external and internal information are brought together, guiding an organism’s behavior; and the cognitive niche: the subjective perspective of the organism, the umwelt of animal behavioral ecology.

Triadic niche construction is the process by which changes in one of these niche domains leads to reciprocal changes in the others. For instance, changes in the food sources used by an early human community (for example, from seeking out fruit to cooperatively hunting large mammals) corresponded to changes in how humans move through the landscape, what they perceive and desire from their environment, and how they conceptualize themselves in relation to their community. Further, changes in the cognitive niche, such as increasing in-group love and out-group fear, likely occurred through changes in human’s ability to perceive and remember familiar faces, made possible through changes in the neural “niche” – all of which could have been in response to changes within the ecological niche. These examples underscore the dynamic relationship between our environment, our cognition, and the neural architecture through which we respond to our contexts – highlighting the reciprocal influence of brain, body and world in shaping the trajectory of human evolution.

One example of triadic niche construction, provided by Iriki and Taoka, is that of world-perception and target acquisition. While humans are not unique among great apes as two-legged upright walkers, the authors suggest that throughout the evolution of animals, we can see increasing complexity of the cognitive niche (the organism’s understanding of its environment) through changes in how different bodies are shaped. The relationship between the body and the mind is one of actor and act – the mind is composed of an organism’s experiential environment, its needs, its ability to predict environmental patterns, and its ability to respond coherently to challenges. The mind evolves as the body does – evolving in parallel with the body’s changing capacity to act. Thus, as an organism’s body plan changes to fit its ecological niche, so must its cognitive niche change to perceive and persist in its environment.

Figure 4 from Iriki and Taoka, showing the evolutionary journey of reaching-and-grabbing motions, highlighting the changing relationship between mouth, eyes, and organs used to grab, as well as the axis of the body.

A worm, a fish, and a frog may each live in different environments – a 3 dimensional space that each must explore in order to acquire food. Yet, due to their similarity — each possessing a mouth, only moving and eating in one direction, each living in an environment guided by their perceptions — the neural architecture needed to survive is similar. As new body plans arise, whether through ecological change or through chance mutation, the internal neural and cognitive niche must change in suit. With the evolution of long necks and the ability to survey surroundings, animals gained new possibilities for perceiving and comprehending their environment; this allowed dinosaurs (and their descendents, the birds) to thrive in their terrestrial environments. Our ancestors, including simians, primates, and great apes, further provided neural and cognitive adaptations necessary for their arboreal lives – using their arms increasingly to climb trees and grab fruit, their minds developed complex mental maps needed to navigate dense forests, to assess their ability to jump between trees, and to perceive threats both on the forest floor and up in the sky above. From monkeys to humans, we see one additional step: upright, bipedal movement. This created new problems in coordination and navigation – in overcoming these difficulties, the human brain has come to develop intricate mental models of the human body in its environment.

The human — standing and walking upright, eyes facing forward with a neck positioned to surveil the environment, hands capable of manipulating tools of all kinds, a brain adapted to social learning — has evolved to extend the faculties that enable spatial navigation and personal attachment into new means for navigating the social, ecological, and increasingly spiritual dimensions of Life. The human mind is built up of innumerable adaptive and (increasingly) antiquated instincts and faculties – but only through our long evolutionary history do we recognize what is truly new about our species. It is through this evolutionary trajectory that we can come to recognize the profound interconnections between human bodies, brains, tools, and communities. The dynamic ecological ramifications of changes in the cognitive, social and technological faculties have come to enable human communities to thrive, increasingly allowing people to constructively participate in shaping their niche.

While Iriki and Taoka’s article delves far deeper into the complex evolution of the human mind — with a key focus on how our minds and tools have coevolved — my main intention with this article is to lay out these two key papers as they shaped the development of my understanding of the human niche and niche construction. Iriki and Taoka’s 2012 article certainly shaped far more than just my understanding of reciprocal processes that construct our niche – their elaborate schema exploring the incremental development of the human brain and our use of tools certainly shaped how I understand our relationship to technology as a whole. But that’s enough science for me today. I will leave you with two figures from the article that elaborate on this complex topic. Please feel free to struggle with them here, or to read them in their proper context through the link below – or to just skip them! Regardless, I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Alright, I suppose I will give a bit of context. These two figures collectively serve to visualize how human tool-use (ranging from simple tools that extend our ability to reach, to more complex tools such as those that shape how we perceive or comprehend the world) created the context that iteratively shaped the human brain, enabling the “higher-order” cognition we associate with humankind. I’ll leave the rest for you to puzzle out.

Through this article, it is my hope that you will have gained a deeper understanding of the reciprocal feedback loops that act as the contours upon which human evolution has flowed. Through exploring how the human body and our tools have led to specific neural and cognitive adaptations and illustrating how these changes reciprocally interact to dynamically shape our social and ecological communities, I hope to have shed a light on the interconnected systems that encompass our place in the world. By acknowledging the constitutive feedback intrinsic to life and embracing the responsibility intrinsic in our tools and our ecological impacts, we can chart a course toward a more sustainable and harmonious future. So let us continue to explore, question, and learn; for in understanding our niche, we gain a deeper understanding of the ethics implicit in human life, and the responsibility we have in shaping the future of our community.

Thank you for reading Jewish Ecology. This blog aims to build a participatory dialogue in which important ideas at the intersection of Judaism and ecology can help us root ourselves in the World. This blog is not just for Jews; I aim for these articles to be accessible and impactful for anyone that is interested in building up an understanding of the role that spirituality, philosophy, and/or ethics play in bringing about a more peaceful, ecological, and sustainable future for all People and the World.

Sources:

Baedke, J., Fábregas-Tejeda, A. & Prieto, G.I. Unknotting reciprocal causation between organism and environment. Biol Philos 36, 48 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-021-09815-0

Iriki, Atsushi & Taoka, Miki. Triadic (ecological, neural, cognitive) niche construction: a scenario of human brain evolution extrapolating tool use and language from the control of reaching actionsPhil. Trans. R. Soc. B36710–23 (2012). http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0190